We need to stop innovating in Indigenous housing and get on with Closing the Gap

- Written by Kieran Wong, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, Monash University

The tenth anniversary of the launch of the Council of Australian Governments’ (COAG) Closing the Gap agenda came and went, with the usual (often exasperated) commentators noting the lack of progress. The Australian Human Rights Commission was critical in its assessment, noting that:

… a December 2017 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare report found the mortality and life expectancy gaps are actually widening due to accelerating non-Indigenous population gains in these areas.

I’ve been reflecting on some of the wins and losses for architects in the realm of Indigenous housing. Housing underpins many of the Closing the Gap goals, including healthy living, infancy and early childhood education, and strong communities.

Read more: We won't close the gap if the Commonwealth cuts off Indigenous housing support

Individuals such as the late Paul Pholeros and his partners at Health Habitat, along with 30 years of applied research by firms like Troppo and the Centre for Appropriate Technology (CAT), have shaped the way we design housing for health in Indigenous communities. Critical to this work have been statistical and evidence-based approaches to ensuring better design and construction, along with feedback from locally led repair and maintenance programs. A great example is Health Habitat’s long-running Survey Fix projects.

Paul Pholeros’s response to the question of how to reduce poverty? Fix homes.These projects are a long way from the cliché of “hero” architecture that works at the scale of the object and not the community. Architects working in this space are often at the front line of disadvantage in Australia. They are looking for ways, big and small, to make the Closing the Gap Strategy work through architecture, settlement planning and infrastructure.

Houses such as this one designed by Troppo Architects in Angurugu, East Arnhem Land, may not be celebrated as ‘hero’ architecture, but have been carefully designed to meet best practice guidelines for healthy living.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Houses such as this one designed by Troppo Architects in Angurugu, East Arnhem Land, may not be celebrated as ‘hero’ architecture, but have been carefully designed to meet best practice guidelines for healthy living.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Put evidence-based guidelines to work

A key document that captured much of this knowledge was first produced in 1999 by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, a Commonwealth agency abolished in 2005. The third edition of the National Indigenous Housing Guide (NIHG) was released in 2007 and was due to be updated and reviewed in 2009. The COAG National Partnership Agreement on Remote Housing mandated its use but did not legally enforce it.

The result has been a wide divergence from many of the guide’s key recommendations. And without regular updates, the NIHG has fallen into disuse.

In 2013, Health Habitat published its own Housing for Health – The Guide. But neither this online resource nor the NIHG has been a legally enforceable, mandated requirement for housing design and delivery in Indigenous housing.

And thus, despite decades of research and clear evidence, the requirements for expedited rollouts of housing projects often usurp high-quality housing design, community engagement and construction and maintenance. Often this is to suit political timeframes and programs conceived outside the communities they’re meant to serve.

Poor design and lack of regular maintenance soon result in housing being unfit for occupation. The examples above and below are in Angurugu and Yenbakwa, East Arnhem Land.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Poor design and lack of regular maintenance soon result in housing being unfit for occupation. The examples above and below are in Angurugu and Yenbakwa, East Arnhem Land.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

The quality and appropriateness of any project’s procurement model, from engagement to design to delivery, is essential to success. Unfortunately, the delivery of housing into Indigenous communities has tended to be idiosyncratic and driven by shortsighted ambitions – often badged as “innovation”.

Remote Indigenous communities are littered with failed attempts at “housing innovation”. Modular carcasses are dropped in like aliens to meet a particular cost model, or by the whim of a procurement process focused on delivery speed over long-term life cycle and quality.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

The quality and appropriateness of any project’s procurement model, from engagement to design to delivery, is essential to success. Unfortunately, the delivery of housing into Indigenous communities has tended to be idiosyncratic and driven by shortsighted ambitions – often badged as “innovation”.

Remote Indigenous communities are littered with failed attempts at “housing innovation”. Modular carcasses are dropped in like aliens to meet a particular cost model, or by the whim of a procurement process focused on delivery speed over long-term life cycle and quality.

An abandoned housing prototype in Alyungula, East Arnhem Land. Designed to be erected within days, the modular and prefabricated house was deemed unsafe for human habitation within a matter of years.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Learn from the proven mainstream model

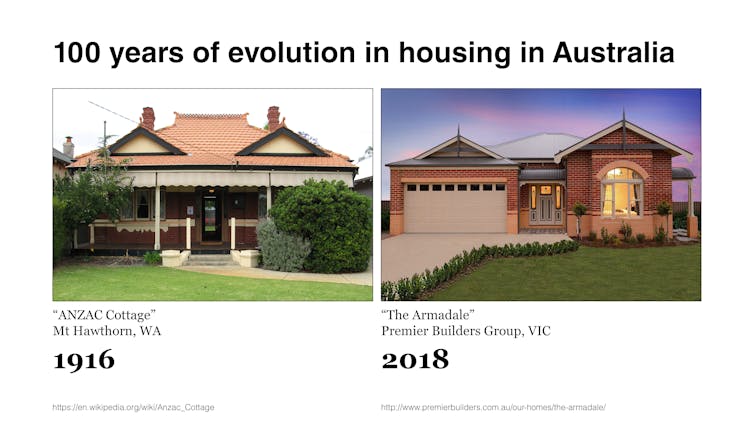

This is in stark contrast to the mainstream mass housing market, which has been well served by designers and builders gradually and systematically improving design solutions, construction techniques and delivery models.

Mainstream housing has evolved incrementally over the past two centuries, with many design and delivery techniques largely unchanged. Despite a substantial increase in size of dwellings (now thankfully on the decline), the average “project home” in Australia is largely designed and built in the same way as it was for our parents, and their parents, brick by brick with coordinated and overlapping trades.

An abandoned housing prototype in Alyungula, East Arnhem Land. Designed to be erected within days, the modular and prefabricated house was deemed unsafe for human habitation within a matter of years.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Learn from the proven mainstream model

This is in stark contrast to the mainstream mass housing market, which has been well served by designers and builders gradually and systematically improving design solutions, construction techniques and delivery models.

Mainstream housing has evolved incrementally over the past two centuries, with many design and delivery techniques largely unchanged. Despite a substantial increase in size of dwellings (now thankfully on the decline), the average “project home” in Australia is largely designed and built in the same way as it was for our parents, and their parents, brick by brick with coordinated and overlapping trades.

Housing in Australia has undergone incremental ‘evolutionary’ change over the past century.

Kieran Wong

Housing in Australia has undergone incremental ‘evolutionary’ change over the past century.

Kieran Wong

Community consultation on Bickerton Island, East Arnhem Land.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Most importantly, mainstream housing has been delivered under continually improving legislative frameworks, such as the Building Code of Australia.

To ensure we stop “innovating” in this space, we must go back to what we know works, to the evidence-based solutions of better housing for health. We must ensure that design processes are co-designed within the affected community, allowing enough time for genuine and effective consultation.

Read more:

Indigenous communities are reworking urban planning, but planners need to accept their history

An example of the iterative and evolutionary process that lies at the heart of mainstream housing is the Building Code of Australia (BCA). Developed through the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) – itself a product of COAG and an inter-governmental agreement – the BCA sets minimum standards and performance criteria for all construction in Australia.

The Building Codes Board has outlined its approach to updating its own document:

The BCA amendment process follows an agreed procedure that is both consultative and transparent, while respecting confidentiality. It includes preparation of detailed technical proposals and, as required under COAG (Council of Australian Governments) arrangements, rigorous impact analysis and broad community consultation to inform decision makers.

Imagine if an updated National Indigenous Housing Guide required the same level of governance, regulatory oversight and commitment by all three tiers of government. The NIHG could be developed in this manner, consistent with the principles of Closing the Gap. It would be enforceable in all jurisdictions through a cohesive and robust design framework for better health in Indigenous housing and communities.

This should be a no-brainer if COAG is seriously committed to Closing the Gap.

Read more:

Why the housing shortage exacerbates scabies in Indigenous communities

Community consultation on Bickerton Island, East Arnhem Land.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

Most importantly, mainstream housing has been delivered under continually improving legislative frameworks, such as the Building Code of Australia.

To ensure we stop “innovating” in this space, we must go back to what we know works, to the evidence-based solutions of better housing for health. We must ensure that design processes are co-designed within the affected community, allowing enough time for genuine and effective consultation.

Read more:

Indigenous communities are reworking urban planning, but planners need to accept their history

An example of the iterative and evolutionary process that lies at the heart of mainstream housing is the Building Code of Australia (BCA). Developed through the Australian Building Codes Board (ABCB) – itself a product of COAG and an inter-governmental agreement – the BCA sets minimum standards and performance criteria for all construction in Australia.

The Building Codes Board has outlined its approach to updating its own document:

The BCA amendment process follows an agreed procedure that is both consultative and transparent, while respecting confidentiality. It includes preparation of detailed technical proposals and, as required under COAG (Council of Australian Governments) arrangements, rigorous impact analysis and broad community consultation to inform decision makers.

Imagine if an updated National Indigenous Housing Guide required the same level of governance, regulatory oversight and commitment by all three tiers of government. The NIHG could be developed in this manner, consistent with the principles of Closing the Gap. It would be enforceable in all jurisdictions through a cohesive and robust design framework for better health in Indigenous housing and communities.

This should be a no-brainer if COAG is seriously committed to Closing the Gap.

Read more:

Why the housing shortage exacerbates scabies in Indigenous communities

Settlement planning discussions – this one is in Umbakumba, East Arnhem Land – offer insights into family mobility patterns and are important to guide future housing.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

We cannot afford to “innovate” in this space, with novel designs or construction techniques that satisfy a short-term need. When the Commonwealth commits to another long-term national funding program for Indigenous housing – and it must – it should draw on the wealth of existing research, evidence, design guidance and project experience.

Importantly, the use of an updated National Indigenous Housing Guide must be mandated in law to ensure the very best housing responses are delivered for our nation’s First Peoples.

The time frames required to make and maintain meaningful change in this space are long. Our governments must seriously invest in this process and commit to starting that journey now.

Settlement planning discussions – this one is in Umbakumba, East Arnhem Land – offer insights into family mobility patterns and are important to guide future housing.

Kieran Wong, CC BY-SA

We cannot afford to “innovate” in this space, with novel designs or construction techniques that satisfy a short-term need. When the Commonwealth commits to another long-term national funding program for Indigenous housing – and it must – it should draw on the wealth of existing research, evidence, design guidance and project experience.

Importantly, the use of an updated National Indigenous Housing Guide must be mandated in law to ensure the very best housing responses are delivered for our nation’s First Peoples.

The time frames required to make and maintain meaningful change in this space are long. Our governments must seriously invest in this process and commit to starting that journey now.

Authors: Kieran Wong, Adjunct Senior Research Fellow, Monash University