how Priya Satia's Time’s Monster landed like a bomb in my historian's brain

- Written by Yves Rees, Lecturer in History, La Trobe University

In this series, writers nominate a book that changed their life – or at least their thinking.

I’ve always wanted to be a historian. From childhood, I was captivated by the idea of spending my days bringing the past to life. At first, I aspired to be a historical consultant on BBC period dramas. Later, I set my sights on becoming a professor.

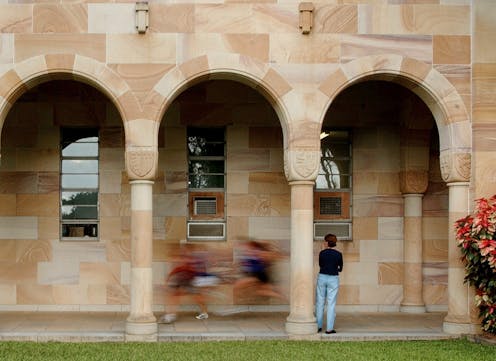

I’ve dedicated my adult life to this goal. I jumped straight into studying history after leaving school and never really stopped. Over the 17 years since I was 17, there’s only been a single semester when I wasn’t a student or employee of a university history department.

If right-wing pundits are to be believed, this means my formative years have been spent amidst “cultural Marxists” bent on revolution. In the conservative imagination, humanities departments are where vulnerable youth are brainwashed into a radical leftist agenda. Of course, as those inside higher education know, this is a laughable notion. Today’s universities are neoliberal bureaucracies, profit-driven enterprises more akin to a giant corporation than a cultural wing of the communist party.

Read more: Is 'cultural Marxism' really taking over universities? I crunched some numbers to find out

Yet, it’s also true that, on this continent, the history profession is a self-consciously “progressive” domain. We critique the drum-beating nationalism of Anzac mythology. We’re proud of the discipline’s role in forcing truth-telling about frontier violence. We call for greater care for our environment and question the inequities of capitalism. Feminism is embraced and women loom large among the professional leadership.

All this makes it easy to imagine historians as the good guys, truth-tellers on the right side of history. All this made it easy for me to assume innocence and pretend my own craft of history-making is removed from the bloody histories we interrogate.

Of course, I’d long known that the university and its pursuit of knowledge was part of the colonial project. I knew archaeologists had stolen Indigenous remains and anthropologists had constructed Indigeneity as a savage Other. I understood that racism was given legitimacy by scientists measuring skulls.

But I stopped short of asking how my own discipline was and remains implicated in this colonising work. A century ago, historians had celebrated powerful white men and omitted everyone else, but surely things were different these days? In the 21st century, History (as a discipline) seemed a benign force, a champion of underdogs and a voice of truth and justice.

Blood on its hands

For these reasons, Priya Satia’s Time’s Monster: History, Conscience and Britain’s Empire landed like a bomb in my brain. In this 2020 book, Satia maps how the “historical discipline helped make empire – by making it ethically thinkable”. Far from being innocent observers, “historians were key architects of empire”.