As we celebrate the rediscovery of the Endeavour let's acknowledge its complicated legacy

- Written by Natali Pearson, Deputy Director, Sydney Southeast Asia Centre, University of Sydney

Researchers, including Australian maritime archaeologists, believe they have found Captain Cook’s historic ship HMB Endeavour in Newport Harbour, Rhode Island. An official announcement will be made on Friday.

The discovery is the culmination of decades of work by the Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project and the Australian National Maritime Museum to locate and positively identify the vessel, which had been missing from the historical record for over two centuries. Plans are now under way to raise funds to excavate and conduct scientific testing in 2019.

As the first European seafaring vessel to reach the east coast of Australia, the Endeavour – much like James Cook himself – has become part of Australia’s national mythology. Unlike Cook, who famously met his end on Hawaiian shores, the fate of the Endeavour had long been unknown. The discovery has therefore resolved a long-standing maritime mystery.

In a serendipitous twist, it coincides with two significant dates: the 250th anniversary of the Endeavour’s departure from England in 1768 on its now (in)famous voyage south, and the 240th anniversary of the ship’s scuttling in 1778 during the American War of Independence.

Identifying the Endeavour’s location has been a 25-year processs. Archaeologists initially identified 13 potential candidates in the harbour. Over time, the number of possible sites was narrowed to five.

This month, a joint diving team has worked to measure and inspect these sites, drawing upon knowledge of Endeavour’s size to identify a likely candidate. Excavation and timber analysis is expected to provide final confirmation. Those expecting an entire ship to be recovered will be disappointed, as very little of it remains.

But this is a controversial vessel, and celebrations of its discovery will be tempered by reflection about its complicity in the British colonisation of Indigenous Australian land. While Endeavour played an instrumental role in advancing science and exploration, its arrival in what is now known as Botany Bay in 1770 also precipitated the occupation of territory that its Aboriginal owners never ceded.

Read more: How Captain Cook became a contested national symbol

A ship by any other name …

Although Endeavour’s early days are well known, it has taken many years for researchers to piece together the rest of its story. One problem has been the many names the vessel was known by during its lifetime.

Built in 1764 in Whitby, England, as a collier (coal carrier), the vessel was originally named Earl of Pembroke. Its flat-bottomed hull and box-like shape, designed to transport bulk cargo, later proved helpful when navigating the treacherous coral reefs of the southern seas.

Endeavour, then known as Earl of Pembroke, leaving Whitby Harbour in 1768. Painting by Thomas Luny, c. 1790. (Some think Luny painted another ship after Endeavour became famous.)

Wikimedia

Endeavour, then known as Earl of Pembroke, leaving Whitby Harbour in 1768. Painting by Thomas Luny, c. 1790. (Some think Luny painted another ship after Endeavour became famous.)

Wikimedia

In 1768, Earl of Pembroke was sold into the service of the Royal Navy and the Royal Society. It underwent a major refit to accommodate a larger crew and sufficient provisions for a long voyage. In keeping with the ambitious spirit of the era, the vessel was renamed His Majesty’s Bark (HMB) Endeavour (bark being a nautical term to describe a ship with three masts or more).

Endeavour departed England in 1768 under the command of then-Lieutenant Cook. Ostensibly sailing to the South Pacific to observe the 1769 Transit of Venus, Cook was also under orders to search for the fabled southern continent. So it was that a coal carrier and a rare astronomical event changed the history of the Australian continent and its people.

Read more: Transit of Venus: a tale of two expeditions

Mysterious ends

Following Endeavour’s circumnavigation of the globe (1768-1771), the vessel was used as a store ship before the Royal Navy sold it in 1775. Here, the ship’s fate become mysterious.

Many believed it had been renamed La Liberté and put to use as a French whaling ship before succumbing to rotting timbers in Newport Harbour in 1793. Others rejected this theory, suggesting instead that Endeavour had spent her final days on the river Thames.

A breakthrough came in 1997. Australian researchers suggested the Endeavour had in fact been renamed Lord Sandwich. The theory gained weight following an archival discovery by Kathy Abbass, director of the Rhode Island project, in 2016, which indicated that Lord Sandwich had been used as a troop transport and prison ship during the American War of Independence before being scuttled in Newport Harbour in 1778.

Lord Sandwich was one of a number of transport ships deliberately sunk by the British in an attempt to prevent the French fleet from approaching the shore.

Finding a shipwreck is not impossible, but finding the one you’re looking for is hard. Rhode Island volunteers have been searching for this vessel since 1993, slowly narrowing down the search area and eliminating potential contenders as they explore the often-murky waters of Newport Harbour.

They were joined in their efforts by the Australian National Maritime Museum in 1999 and, in more recent years, by the Silentworld Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation with a particular interest in Australasian maritime archaeology.

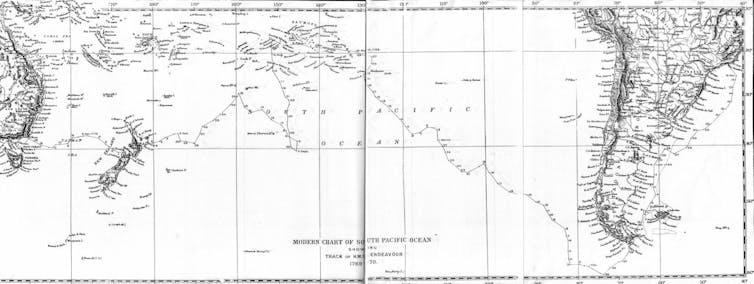

Endeavour’s voyage across the Pacific Ocean.

Wikimedia

Endeavour’s voyage across the Pacific Ocean.

Wikimedia

Museums around the world are already turning their attention to the significant Cook anniversaries on the horizon and the complex legacy of these expeditions. These interpretive endeavours will only be heightened by the planned excavation of the ship’s remains in the near future.

Shipwrecks are a productive starting point for thinking about how we make meaning from the past because of the firm hold they have on the public imagination. They conjure images of lost treasure, pirates and, especially in the case of Endeavour, bold adventures to distant lands.

But as we celebrate the spirit of exploration that saw a humble coal carrier circumnavigate the globe – and the same spirit of exploration that has led to its discovery centuries later – we must also make space for the unsettling stories that will resurface as a result of this discovery.

Authors: Natali Pearson, Deputy Director, Sydney Southeast Asia Centre, University of Sydney