The Australian war film Jirga is a lesson in Afghan forgiveness

- Written by Ehsan Azari Stanizai, Lecturer in literary studies, National Institute of Dramatic Art

Review: Jirga

It is cathartic when a war movie takes us far beyond the horror of bullets, bomb and blood into the other side of the battlefield — the emotional impact on individuals.

The Australian production Jirga mines the depth of the heartache and guilt experienced by an Australian ex-soldier whose conscience has caught up with his participation in a night raid on a desolate hamlet in Kandahar. In doing so, it moves away from run-of-the-mill cinematic depictions of this war, laden with stereotypical, nationalistic hubris.

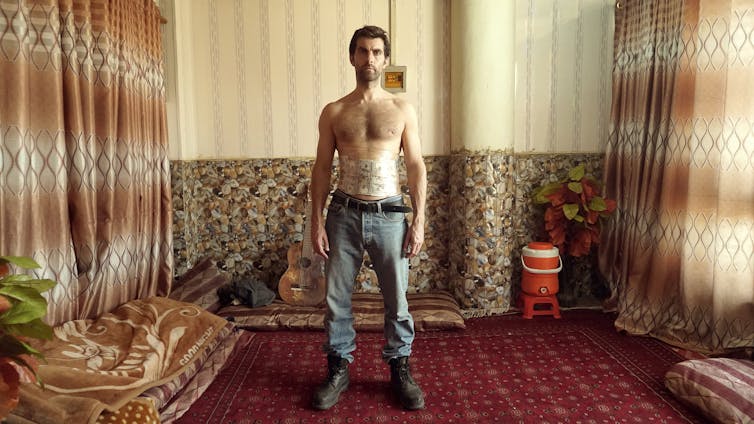

Jirga is the story of Mike Wheeler, who kills an unarmed civilian in a thundery, blazing raid on a far-flung village in southern Afghanistan. Three years later, he travels to the same village, seeking forgiveness.

Sam Smith as Mike Wheeler: a former soldier who killed an unarmed civilian in a night raid in Kandahar.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

Sam Smith as Mike Wheeler: a former soldier who killed an unarmed civilian in a night raid in Kandahar.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

Sam Smith plays Wheeler admirably. Early in the film, he turns back and looks ruefully at his victim’s body, which is being dragged home by his wife and a child. Later, back in Kabul, he makes friends with a taxi driver, played by Sher Alam Miskeen Ustad, who sometimes sings while driving.

Wheeler begs the driver to take him to Kandahar, the Afghan historical city named by Alexander the Great now regarded as a highly dangerous place. The cabbie vehemently resists the request. Eventually, after an offer of considerable money, he agrees to drive Wheeler into the most dangerous terrain infested with Taliban militants.

Cabbies are famous for their gift of the gab. You can charm them, wrote the Italian philosopher and semiotician, Umberto Eco, by punctuating the conversation with “frequent interjections on the order of ‘it’s a crazy world!’.” This is what the hashish-smoking cabbie says in his beautiful Pashtu songs:

Like streams, tears roll past my collar down my neck,

This is a crazy brutal world, there is no one to have mercy on me.

Along their journey, Wheeler is stopped at a Taliban check point but he manages to flee when their barrage of bullets misses him. The second time, he isn’t so lucky. Captured by the Taliban he is taken to their mountain hideout. They are divided as to whether to kill him or demand a huge ransom for his release.

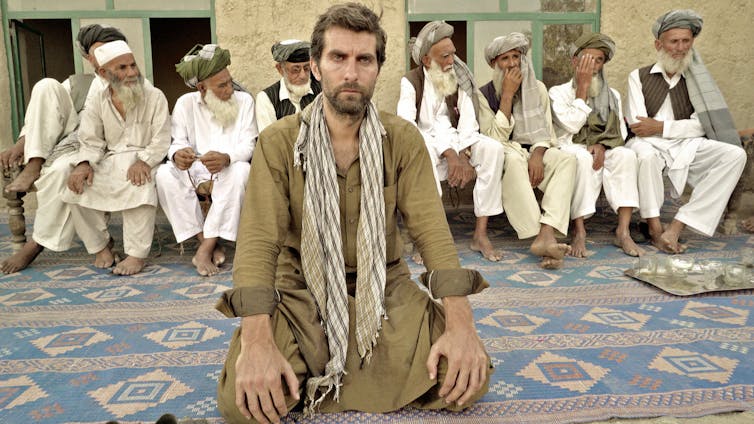

The Taliban’s commander decides to leave the villagers to pass a verdict on Wheeler’s fate in their Jirga — the traditional assembly, part of the non-written, age-old Afghan ethical code of honour, Pashtunwali.

Mike Wheeler (Sam Smith) at the Jirga.

Felix Media,Screen Australia

Mike Wheeler (Sam Smith) at the Jirga.

Felix Media,Screen Australia

The Jirga unanimously passes a resolution that the only one who is able to forgive or kill Wheeler is a 10-year-old orphan of the dead villager. Wheeler’s statement, to use once he is confronted with the villagers, is translated into Pashtun: “I killed someone, please forgiveness.”

When Wheeler knocks at the door of his victim’s family, he realizes that the person he killed was, in fact, the village musician. In a highly emotional scene, while all eyes are on him, the dead man’s son pensively gazes at the soldier. Then he sheathes his dagger.

The dead man’s son.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

The dead man’s son.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

“Forgiveness is mightier and [more] honourable than taking revenge,” the jubilant villagers burst into shouts. They then slaughter a ram on behalf of Wheeler — a ceremonious symbol of forgiving the enemy. The orphan also refuses to accept wads of the US dollars the ex-soldier offers as blood money. So finally, forgiveness and compassion win over revenge — a virtue in Afghan tribal culture.

American director Peter Berg previously brought the code of honour, Pashtunwali, to screen in his war movie, Lone Survivor (2013), and combined it with a hyped-up American nationalism.

However, Jirga’s director Benjamin Gilmour depicts a bare-bones portrayal of the Afghan tradition. The rich and dense imagery of the rugged beauties of the Afghan mountains, eerie gorges, and the penetrating sound of the Afghan Rubab mingled with Western chillout music shine, as does the innovative cinematography.

Jirga has a clear message to everyone - the Taliban, the Westerners, and the Afghans - even in the horror of warfare you can’t escape moral accountability.

Taliban soldiers in Jirga.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

Taliban soldiers in Jirga.

Felix Media, Screen Australia

And indeed, in his trials and tribulations, Wheeler isn’t alone. Gilmour gives his own account, as a story-within-the-story, of his struggles experienced while making it.

To avoid risking their lives by filming in Afghanistan, Gilmour and his crew first travelled to Pakistan to shoot the film in the tribal area along the Durand Line, the imaginary and disputed border between Afghanistan and Pakistan.

A sympathetic person in Pakistan was ready to fund the film’s production to the tune of $100,000. But after reading its screenplay, the infamous Pakistani military spy agency, the ISI rejected Gilmour’s plan to film there, which led to the financier pulling out of the deal.

The film maker and his crew then decided to shoot Jirga in the most dangerous place on earth, Kandahar, at all costs.

A screening of Jirga followed by a Q&A with director Benjamin Gilmour, lead actor Sam Smith and producer John Maynard, will be held at Hayden Orpheum Picture Palace in Sydney on September 20 at 6.30pm. Jirga opens in Australian cinemas on September 27.

Authors: Ehsan Azari Stanizai, Lecturer in literary studies, National Institute of Dramatic Art

Read more http://theconversation.com/the-australian-war-film-jirga-is-a-lesson-in-afghan-forgiveness-99738