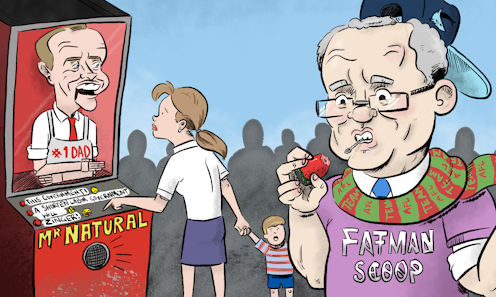

how our leaders work hard at being 'ordinary'

- Written by Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Is it sufficiently dignified to call a prime minister, as distinct from an immigration minister or treasurer, ScoMo? Is this part of Scott Morrison’s “ordinary bloke” persona? It does sound a bit like Joe Shmoe, which Wikipedia tells me means “no one in particular” and “is one of the most commonly used fictional names in American English”. But it also sounds a bit Hollywood, evoking JLo.

So it may well be the kind of game that virtually every politician with serious leadership aspirations has to play. They need to convince us that they are not so far above us that they are out of touch. (“How much is a litre of milk, Prime Minister?”) Yet when they do present themselves as just like us, we can’t really take them seriously. We do, in the end, expect our leaders to be different.

Each leader plays the game differently. William Shorten is, of course, Bill – who tweeted about doing the shopping with his young daughter on Father’s Day.

Minus the shopping trolley, Robert Menzies and Robert Hawke were both Bob, and William Hughes and William McMahon were Billy. Curtin was Jack to his mates but John to the public. Chifley was Ben to all, and the unassuming Lyons was happy enough with Joe. It was hard to do much with Gough or Paul, and Malcolm Fraser only became Mal when he was being ridiculed. Everyone knew he was no Mal, and nor was Turnbull. “Johnny Howard” was almost never complimentary, especially when preceded by “Little”, and Kevin might have been from Queensland and here to help, but he never became Kev – not even when worrying over the shaking of sauce bottles – any more than Julia became Jules.

Politicians have long fretted over these matters. When the future prime minister, Stanley Melbourne Bruce, became prime minister, he issued a note to the press:

Mr Bruce would be very glad if the newspapers would not refer to him by his Christian name, as Mr Stanley Bruce, but always as Mr S.M. Bruce.

Today’s journalists, cartoonists and comedians – to say nothing of one’s political opponents - would be in raptures if a newly minted prime minister issued such a notice. And it was clearly unthinkable that the golf-playing, spats-wearing Bruce would be just plain Stan.

Here is a reminder that there is more than one way of performing the role of Australian prime minister. The late political psychologist Graham Little used to give a set-piece lecture on political leadership at Melbourne University, whose major details I can still recall 30 years later – so it must have been good.

Little thought there were broadly three types. Margaret Thatcher was a “strong leader” – the children’s TV program that demonstrated the style was Romper Room. Boys wore boys’ clothes and looked like boys. Girls wore girls’ clothes and looked like girls. Miss Helena dressed conservatively and had a mirror through which she could keep an eye on us at home. Moral codes were strictly defined, with the help of Mr Do Bee (“Do be an asker. Don’t be a help yourself”). Good conduct included being able to walk around with a basket balanced on your head.

“Inspiring leadership” was exemplified by Gough Whitlam – and Play School. Each, in turn, went out of their way to demonstrate good, inclusive citizenship, and creative, inclusive play, yet without pretending to become an ordinary citizen, or an ordinary child.

Like Miss Helena, Play School leaders were grownups. But unlike her – and like Whitlam – they spoke to their audience of children as intelligent equals, dressed a bit like kids (possibly in overalls, not skirts, for women) and played along with them rather than laying down the law. Big Ted was a more gentle soul than Mr Do Bee – who presumably had a sting. Gender differences are more frankly acknowledged, but explored rather than taken for granted.

Read more: What kind of prime minister will Scott Morrison be?

And then there were “group leaders”, like Bob Hawke – and Humphrey B. Bear. Humphrey, seemingly male yet somewhat ambiguously defined, runs around without trousers (any resemblance here to an Australian prime minister, living or dead, being purely coincidental). He is also a child, not an adult, and to this extent he shares a common identity with his audience. But they are not entirely deceived: Humphrey’s not really the same as the kids watching at home. In short, he’s rather like Hawke, who at his best convinced us that he was one of us even while being unmistakably “special”.

Not all have even attempted this balancing act. Neither Bruce nor Menzies ever pretended to be everyman, although Menzies occasionally pointed to his humble origins as the son of a country storekeeper. Keating barely made the effort; his adoption of Collingwood Football Club when he became prime minister was widely ridiculed for its cynicism, coming as it did from a man whose interests ran more to classical music and French clocks.

Malcolm Turnbull’s leather jacket, never entirely convincing, did not survive his elevation to prime minister. His persona in the job more resembled a Renaissance Florentine merchant-statesman – albeit without the art or culture, which may well have been Turnbull’s major concession to the common folk.

Like Keating, the very Sydney-ish Morrison is looking south for an AFL club, and he has cultivated what journalist Phillip Coorey calls a “daggy ordinariness”. But his everyman act is already running up against his evangelical Christianity. The classic Australian plain man is not an evangelical.

Russel Ward sketched the “the typical Australian” most influentially in The Australian Legend 60 years ago. He is, Ward writes, “sceptical about the value of religion and of intellectual and cultural pursuits generally”. The latter certainly fits Morrison, but not the former.

That said, he leads Shorten as preferred prime minister in Newspoll. It is worth pausing to ask why Shorten, former Australian Workers’ Union leader, has never been able to break through as a personally popular figure. He has clearly modelled aspects of his career on Hawke, but no one would ever accuse him of possessing Hawke’s charisma. He will never approach his stratospheric approval ratings. Perhaps there are too many stories around of his cosy relations with filthy rich businessmen.

He became a national figure on the back of his media profile during the Beaconsfield mine disaster and rescue in Tasmania in 2006, and he campaigned most effectively in the 2016 election. Yet he often seems wooden in front of a camera, as distinct from when talking with ordinary voters. On the couple of occasions I’ve witnessed him deliver prepared speeches, he was engaging if not magnetic, and improved as he warmed to the message he was delivering.

Hawke moved in similar business circles to Shorten, and had his deficiencies as both a public speaker and parliamentary performer. But he was brilliant if unpredictable in a TV interview, before he cut the drinking and learned better to control his temper. His media image in the 1970s, while ACTU president, overwhelmed any popular suspicion that he was in the pockets of the top end of town, although there was a growing chorus of complaints about rich mates during his prime ministership.

Shorten, much more than Hawke, has been damaged by the perception of backroom dealing; with bosses, while a union leader, and over the internecine warfare within the Labor Party. Voters might have a sneaking respect for his doggedness – think John Howard – but they don’t love him and probably never will. Nonetheless, they may well elect him.

Authors: Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University