Memories. In 1961 Labor promised to boost the deficit to fight unemployment. The promise won

- Written by Warwick Smith, Research economist, University of Melbourne

Lately, governments and oppositions have been obsessed with “returning to surplus” in order to balance the budget.

It hasn’t always been so. In the lead-up to the 1961 federal election, unemployment had climbed above 2% and was creeping towards 3%. (By today’s standards that doesn’t sound much, but for two decades since the onset of the second world war unemployment had been mostly well below 2%.)

The Labor opposition, led by Arthur Calwell, went to the 1961 election promising that:

Labor will restore full employment within 12 months, and will introduce a supplementary budget in February for a deficit of £100 million, if necessary, to achieve this.

From the end of World War II, there had been a bipartisan commitment to full employment in Australia. As laid out in the Curtin government’s 1945 White Paper, Full Employment in Australia, this was achieved by “stimulating spending on goods and services to the extent necessary to sustain full employment”.

The strongly held view, developed primarily by British economist John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression, was that government could, and should, use its spending power to fill any gap left by private expenditure, ensuring there was always enough spending to keep operating near (but not above) capacity.

Spending stopped unemployment

The 25 years after World War II in which this happened are often referred to as the “postwar boom” because times were so good. This period had rapid economic growth, steadily improving material standards of living (for most), and falling inequality.

Involuntary unemployment was scarcely heard of. “Long-term unemployment” didn’t exist as a statistical category.

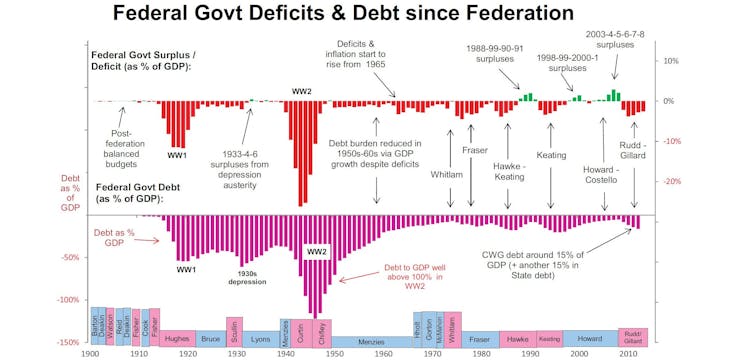

By focusing on keeping the Australian economy at or near full capacity and investing heavily in infrastructure, research and education to improve productivity, the postwar governments of both major parties were able to do what these days would be thought impossible: to run constant government deficits while overseeing a dramatic fall in the ratio of government debt to gross domestic product.

Source: Australian Federal Government deficits, debt and the stock market, Centric Wealth

What’s important to understand is that the postwar boom occurred, at least in part, because of the budget deficits, not in spite of them.

By always spending enough to maintain the economy at full employment, the government ensured a strong economy. Economic growth made the ratio of debt to gross domestic product shrink.

All of this was very much part of the public conversation back in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Very little attention was given to the budget balance, with people instead focused on the level of unemployment. On the rare occasions the budget balance was mentioned, it was often in the context of pushing for greater deficits to reduce unemployment.

Calwell won the fight, if not the election

Source: Australian Federal Government deficits, debt and the stock market, Centric Wealth

What’s important to understand is that the postwar boom occurred, at least in part, because of the budget deficits, not in spite of them.

By always spending enough to maintain the economy at full employment, the government ensured a strong economy. Economic growth made the ratio of debt to gross domestic product shrink.

All of this was very much part of the public conversation back in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s. Very little attention was given to the budget balance, with people instead focused on the level of unemployment. On the rare occasions the budget balance was mentioned, it was often in the context of pushing for greater deficits to reduce unemployment.

Calwell won the fight, if not the election

After the 1961 election Robert Menzies made Arthur Calwell’s policy his own.

National Library of Australia

Calwell’s Labor opposition didn’t win the 1961 election, but there was a massive swing towards it and the result was one of the closest in Australia’s history, decided by mere hundreds of votes.

The fact that unemployment had crept up towards 3% was a significant contributor to the Coalition losing 15 seats in the House of Representatives and control of the Senate.

Immediately after the election, to shore up his position, Menzies effectively adopted and extended Labor’s policy delivering a 1962-63 budget that focused squarely full employment and brought down a deficit £120 million, £20 million more than Labor had been proposing.

The debt burden shrank as GDP climbed

By the end of World War II, government debt was 120% of gross domestic product total. This means that total debt was 1.2 times the annual economic output of the country. By comparison, today’s federal government debt is about 18% of GDP, a mere one-fifth of annual economic output.

So, according to the modern political discourse on government debt, the postwar generations must have been terribly burdened by all of that debt, and governments must have had to show incredible fiscal discipline to pay it off, right?

The answer will surprise many who have fallen for the modern rhetoric. Although each loan was paid off as if came due, the total stock of debt didn’t shrink, but the economy grew strongly, allowing the debt-to-GDP ratio to wither to the point at which it approached zero.

After the 1961 election Robert Menzies made Arthur Calwell’s policy his own.

National Library of Australia

Calwell’s Labor opposition didn’t win the 1961 election, but there was a massive swing towards it and the result was one of the closest in Australia’s history, decided by mere hundreds of votes.

The fact that unemployment had crept up towards 3% was a significant contributor to the Coalition losing 15 seats in the House of Representatives and control of the Senate.

Immediately after the election, to shore up his position, Menzies effectively adopted and extended Labor’s policy delivering a 1962-63 budget that focused squarely full employment and brought down a deficit £120 million, £20 million more than Labor had been proposing.

The debt burden shrank as GDP climbed

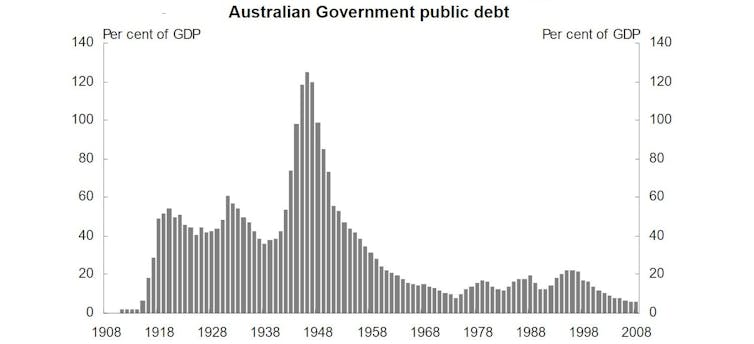

By the end of World War II, government debt was 120% of gross domestic product total. This means that total debt was 1.2 times the annual economic output of the country. By comparison, today’s federal government debt is about 18% of GDP, a mere one-fifth of annual economic output.

So, according to the modern political discourse on government debt, the postwar generations must have been terribly burdened by all of that debt, and governments must have had to show incredible fiscal discipline to pay it off, right?

The answer will surprise many who have fallen for the modern rhetoric. Although each loan was paid off as if came due, the total stock of debt didn’t shrink, but the economy grew strongly, allowing the debt-to-GDP ratio to wither to the point at which it approached zero.

Commonwealth Treasury

Australia’s budget history is one of modest deficits leavened with occasional larger deficits and occasional surpluses. It’s been entirely sustainable.

Our postwar governments lived by Keynes’s dictum:

Look after the unemployment and the budget will look after itself.

The economy has changed a lot since then and we can’t simply copy the policies that worked for Curtin, Chifley and Menzies.

But we can learn from them. The reality is that we don’t know how low unemployment could fall in modern Australia because we haven’t made any genuine attempt to push it below 5% for decades.

Read more:

Explainer: what is modern monetary theory?

A modern-day policy commitment to full employment, along lines inspired by what we did after the war, could lift wages, reduce inequality, drive increases in productivity and, most importantly, provide full employment for the more than two million Australians who are currently unemployed, underemployed or discouraged attempting to get work.

Treasurer Chifley summed up the goal this way in 1944:

Our objective is not primarily social security, but rather the much higher objective of full employment of manpower and resources in raising living standards.

Commonwealth Treasury

Australia’s budget history is one of modest deficits leavened with occasional larger deficits and occasional surpluses. It’s been entirely sustainable.

Our postwar governments lived by Keynes’s dictum:

Look after the unemployment and the budget will look after itself.

The economy has changed a lot since then and we can’t simply copy the policies that worked for Curtin, Chifley and Menzies.

But we can learn from them. The reality is that we don’t know how low unemployment could fall in modern Australia because we haven’t made any genuine attempt to push it below 5% for decades.

Read more:

Explainer: what is modern monetary theory?

A modern-day policy commitment to full employment, along lines inspired by what we did after the war, could lift wages, reduce inequality, drive increases in productivity and, most importantly, provide full employment for the more than two million Australians who are currently unemployed, underemployed or discouraged attempting to get work.

Treasurer Chifley summed up the goal this way in 1944:

Our objective is not primarily social security, but rather the much higher objective of full employment of manpower and resources in raising living standards.

Authors: Warwick Smith, Research economist, University of Melbourne