No, a hug isn't COVID-safe. But if you have to do it, here's what to keep in mind

- Written by Lara Herrero, Research Leader in Virology and Infectious Disease, Griffith University

In the time of COVID, greetings are no longer by handshakes, hugs or kisses on the cheek. An “elbow bump” is the preferred pandemic greeting.

Although COVID transmission in Australia is now minimal and restrictions are easing, keeping 1.5 metres apart from people outside your household is still strongly encouraged — meaning hugging is therefore discouraged.

Some people who live alone may by now have gone months without touching or hugging another person.

While avoiding close contact with others is one of the key measures to prevent virus spread, the irony is we probably need a hug more in 2020 than ever before. So how dangerous is a hug really in the time of COVID?

Human contact is important

Our first contact in life is essentially the hug; newborn babies are constantly cradled, nursed and cuddled.

We are principally social creatures, and this need for human contact continues into childhood and adulthood.

Culturally, hugging plays an important role as an affectionate greeting in many countries.

Its value is clearly demonstrated in European countries such as Italy, France and Spain, where hugging is common. It’s little surprise many Europeans are finding the new way of living with COVID hard to accept.

Australians, too, tend to hug members of their families and close social circle.

Read more: Nice to meet you, now back off! How to socially distance without seeming rude

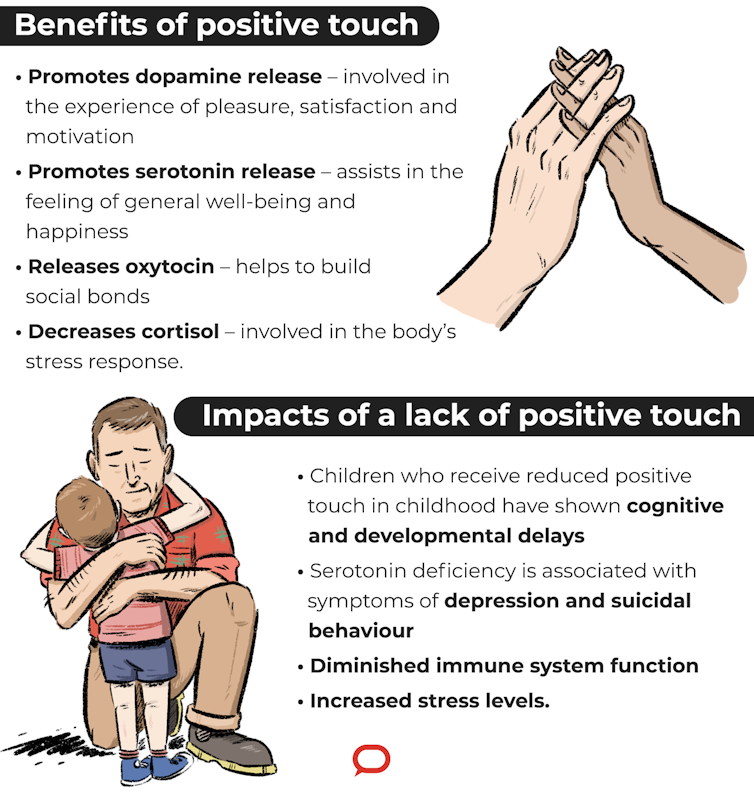

While the act of hugging may give us a feeling of happiness and security, there’s actually science behind the benefits of hugging for our mental health and well-being.

Research shows skin-to-skin contact from birth enables babies’ early ability to develop feelings and social skills, and reduces stress for both mother and baby.

When we hug someone, a hormone called oxytocin is released. This “cuddle hormone” fosters bonding, reduces stress and can lower blood pressure.

Positive touch, such as hugging, also releases the “happy chemical” serotonin. Low levels of serotonin, and of a related happy hormone called dopamine, can be associated with depression, anxiety and poor mental health.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

“Touch deprivation” has become a serious consequence from the pandemic and may have affected many people’s mental health, particularly those living alone or in unstable relationships.

Not only are we missing out on the positive emotions a hug can provide, but we’re not getting the biochemical and physiological benefits either.

Can you hug wisely?

SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, is primarily spread from person to person through respiratory droplets emitted when an infectious person coughs, sneezes, talks or even breathes.

We know we can contract COVID through close contact with an infected person, so the act itself is quite risky if you, or the person you’re hugging, is infectious. But we can’t always identify who has the virus, making the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission via a hug difficult to assess.

Given people who are asymptomatic and presymptomatic have been shown to be able to spread the virus, a simple hug may have serious consequences.

Wes Mountain/The Conversation, CC BY-ND

“Touch deprivation” has become a serious consequence from the pandemic and may have affected many people’s mental health, particularly those living alone or in unstable relationships.

Not only are we missing out on the positive emotions a hug can provide, but we’re not getting the biochemical and physiological benefits either.

Can you hug wisely?

SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, is primarily spread from person to person through respiratory droplets emitted when an infectious person coughs, sneezes, talks or even breathes.

We know we can contract COVID through close contact with an infected person, so the act itself is quite risky if you, or the person you’re hugging, is infectious. But we can’t always identify who has the virus, making the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission via a hug difficult to assess.

Given people who are asymptomatic and presymptomatic have been shown to be able to spread the virus, a simple hug may have serious consequences.

Hugging forms bonds.

Xavier Mouton Photographie/Unsplash

Ultimately, all experts agree: best practice is to avoid physical contact with people not in your own household.

If you absolutely must hug someone, there are some things you should keep in mind to minimise the risk of transmission.

Read more:

Miss hugs? Touch forms bonds and boosts immune systems. Here’s how to cope without it during coronavirus

6 tips to limit the risk

Don’t hug anyone showing COVID symptoms, or if you have any symptoms

don’t hug a vulnerable person (the elderly, immunocompromised and those with other medical conditions), as these people will be at higher risk if they contract COVID

when hugging another healthy person, avoid pressing your cheeks together; instead, turn your face in the opposite direction

wear a mask

hold your breath if you can. That way you can avoid transmitting or inhaling infectious respiratory droplets during the hug

wash or sanitise your hands before and after the hug

Other ways to get your warm and fuzzies

Contact with animals can provide similar mental health benefits to hugging, and also increases oxytocin. These are among the reasons pet therapy is used for people who are elderly or sick.

Maintaining social interactions and connections in the absence of direct touch can help too. Virtual gatherings can have a positive effect on people’s well-being during isolation, and now we’re increasingly able to gather in person again.

The pandemic has made us all realise how important social and physical contact can be to our health and well-being. While we may now appreciate the humble hug more than we did before, for the time being it’s safer to seek emotional support in other ways.

Read more:

'Kissing can be dangerous': how old advice for TB seems strangely familiar today

Hugging forms bonds.

Xavier Mouton Photographie/Unsplash

Ultimately, all experts agree: best practice is to avoid physical contact with people not in your own household.

If you absolutely must hug someone, there are some things you should keep in mind to minimise the risk of transmission.

Read more:

Miss hugs? Touch forms bonds and boosts immune systems. Here’s how to cope without it during coronavirus

6 tips to limit the risk

Don’t hug anyone showing COVID symptoms, or if you have any symptoms

don’t hug a vulnerable person (the elderly, immunocompromised and those with other medical conditions), as these people will be at higher risk if they contract COVID

when hugging another healthy person, avoid pressing your cheeks together; instead, turn your face in the opposite direction

wear a mask

hold your breath if you can. That way you can avoid transmitting or inhaling infectious respiratory droplets during the hug

wash or sanitise your hands before and after the hug

Other ways to get your warm and fuzzies

Contact with animals can provide similar mental health benefits to hugging, and also increases oxytocin. These are among the reasons pet therapy is used for people who are elderly or sick.

Maintaining social interactions and connections in the absence of direct touch can help too. Virtual gatherings can have a positive effect on people’s well-being during isolation, and now we’re increasingly able to gather in person again.

The pandemic has made us all realise how important social and physical contact can be to our health and well-being. While we may now appreciate the humble hug more than we did before, for the time being it’s safer to seek emotional support in other ways.

Read more:

'Kissing can be dangerous': how old advice for TB seems strangely familiar today

Authors: Lara Herrero, Research Leader in Virology and Infectious Disease, Griffith University