Our unis do need international students and must choose between the high and low roads

- Written by John Shields, Professor of Human Resource Management and Organisational Studies, University of Sydney

Australian universities have come to rely heavily on revenue from onshore international students. Numbers more than doubled in the decade to 2018. But the proposition that Australia’s public universities should step back 50 years, retreat from international education and focus wholly or largely on domestic students is naively nostalgic.

Such a move would be a backward step economically, culturally and diplomatically, as a new Asia Taskforce discussion paper concludes. It would diminish Australia and its global standing.

However, 37 of our universities are publicly owned and thus have a social obligation to serve domestic students. It is right that we have a robust debate about the international student presence on our campuses.

Unfortunately, the debate has generated more heat than light. It’s at risk of being hijacked for ideological purposes, rather than generating credible and practical solutions on which the sector and government can act.

Read more: COVID-19: what Australian universities can do to recover from the loss of international student fees

Getting to the root of the problem

Criticisms of the sector aren’t without merit. As some academics have suggested, and as COVID-19 has writ large, universities’ high exposure to the international education market is high risk.

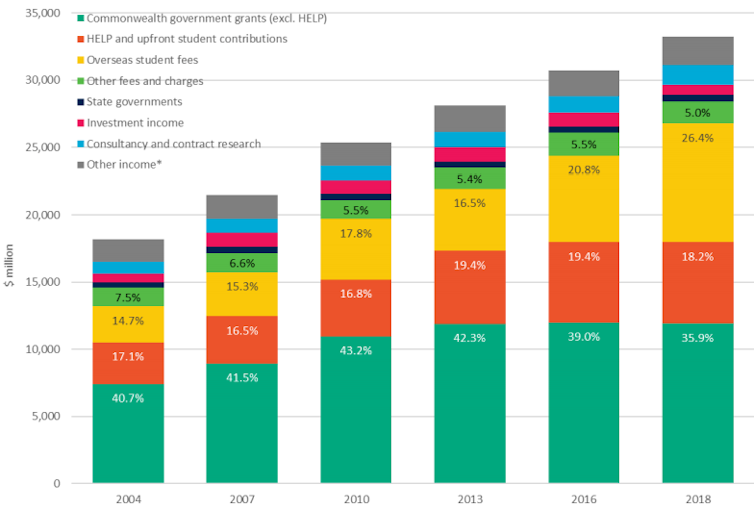

Changes in sources of university revenue from 2004 to 2018 (in 2018 dollars)

Universities Australia, CC BY

Changes in sources of university revenue from 2004 to 2018 (in 2018 dollars)

Universities Australia, CC BY

The proportion of international students per institution in 2018 averaged 22%, ranging from a low of 4% (New England) to a high of 48% (Bond). At some business and engineering faculties, the proportion exceeded 50%.

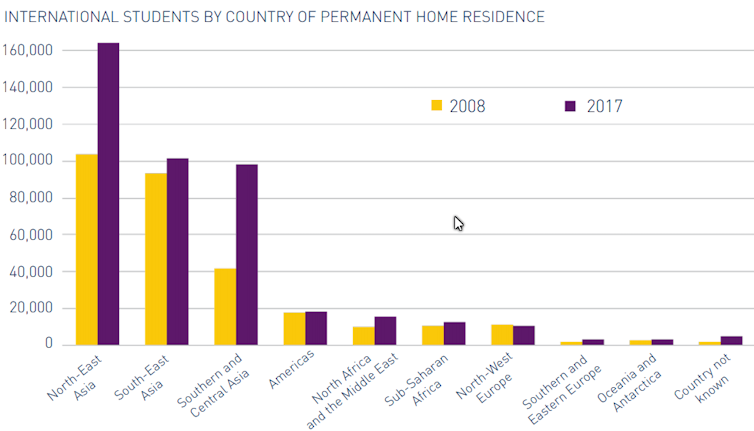

Enrolments at some of our largest universities also have an unacceptable skew towards single countries – either China or India. Some universities, particularly Group of Eight institutions, have fallen into the habit of setting international fees according to what China – the world’s largest student market – will bear. This has eroded competitiveness in more cost-sensitive countries like those in South East Asia and Latin America.

Universities Australia. Data source: DET Selected Higher Education Statistics 2008 and 2017 Student Data

Furthermore, the sector can and must lift its game on all-round educational quality. The issues include academic and English-proficiency admission standards, the quality of the learning experience, and graduate employability and job outcomes.

Whatever the critics might assert, though, the root cause of this reliance is not institutional greed. The underlying driver has been bipartisan attachment to weaning the sector off the public purse and requiring it to stand on its own two feet financially.

Read more:

How universities came to rely on international students

In the two decades to 2015, OECD data suggest Australia slipped from sixth place to 24th among OECD countries in terms of public investment in higher education as a share of GDP. While some dispute these metrics, the flatlining of real direct funding by government has created a university sector that is neither fish nor fowl: publicly owned yet increasingly reliant on commercial income sources.

Fee revenue isn’t the only benefit

A striking feature of criticisms of the international student presence is a refusal to acknowledge its benefits. Education was the nation’s third-largest export earner last year. Higher education alone contributed A$31 billion.

International students contribute greatly to local economies too. They spend on accommodation, food, leisure and entertainment. Over 31,000 jobs rely on the University of Sydney alone.

Falling onshore international student numbers have magnified the pandemic’s impacts. A Mitchell Institute research paper last week forecast a 50% decline in onshore international students by mid-2021. The paper detailed the suburb-by-suburb economic impact on our cities.

Read more:

COVID to halve international student numbers in Australia by mid-2021 – it's not just unis that will feel their loss

The socio-cultural benefits these students bring are also habitually ignored or dismissed.

Neglected, too, are the many benefits and opportunities, including “soft power” projection, that flow from having hundreds of thousands of Australian university alumni worldwide. There are well over 200,000 in China alone.

Low road or high road?

The sector and policymakers now face a stark choice regarding the number, size and student profile of universities. In the post-pandemic world, and in the absence of increased direct government funding per student, the sector must choose between the “low road” and the “high road” to survival and sustainability.

The low road would involve pulling back to a largely or even wholly domestic focus. The results would very likely be sector-wide decline, shrinking universities, deteriorating campus facilities, a lowering of horizons and a reversion to a pre-1990s focus on domestic student education.

Read more:

Without international students, Australia's universities will downsize – and some might collapse altogether

Internationalism would give way to isolationism and educational nationalism of Trumpian proportions. This path would consign the sector to a future of parochialism, mediocrity and global irrelevance.

Alternatively, the sector could take the “high road”. This would involve repositioning itself as a high-quality provider of new forms of learning for both international and domestic students.

The sector and government would have to work in partnership to rebuild universities’ global brand and reputation, recover international student numbers and reprofile this student cohort. The latter step would aim both to improve the academic merit of students from China and diversify intakes.

The high road is also the hard road. It requires a pro-active (not defensive) mindset and an all-round shift in perceptions of Australia, Australians and our universities. But it may well set the sector on a bright new path.

The hope that a surge in domestic student demand will save the sector from atrophy is delusional. The government must either greatly increase recurrent funding per student or provide strong tactical support to recover and diversify international student enrolments. The latter approach would enable the sector to continue to cross-subsidise degree studies by domestic students, fund high-quality research, and develop campus and IT infrastructure fit for the fourth industrial revolution.

Universities Australia. Data source: DET Selected Higher Education Statistics 2008 and 2017 Student Data

Furthermore, the sector can and must lift its game on all-round educational quality. The issues include academic and English-proficiency admission standards, the quality of the learning experience, and graduate employability and job outcomes.

Whatever the critics might assert, though, the root cause of this reliance is not institutional greed. The underlying driver has been bipartisan attachment to weaning the sector off the public purse and requiring it to stand on its own two feet financially.

Read more:

How universities came to rely on international students

In the two decades to 2015, OECD data suggest Australia slipped from sixth place to 24th among OECD countries in terms of public investment in higher education as a share of GDP. While some dispute these metrics, the flatlining of real direct funding by government has created a university sector that is neither fish nor fowl: publicly owned yet increasingly reliant on commercial income sources.

Fee revenue isn’t the only benefit

A striking feature of criticisms of the international student presence is a refusal to acknowledge its benefits. Education was the nation’s third-largest export earner last year. Higher education alone contributed A$31 billion.

International students contribute greatly to local economies too. They spend on accommodation, food, leisure and entertainment. Over 31,000 jobs rely on the University of Sydney alone.

Falling onshore international student numbers have magnified the pandemic’s impacts. A Mitchell Institute research paper last week forecast a 50% decline in onshore international students by mid-2021. The paper detailed the suburb-by-suburb economic impact on our cities.

Read more:

COVID to halve international student numbers in Australia by mid-2021 – it's not just unis that will feel their loss

The socio-cultural benefits these students bring are also habitually ignored or dismissed.

Neglected, too, are the many benefits and opportunities, including “soft power” projection, that flow from having hundreds of thousands of Australian university alumni worldwide. There are well over 200,000 in China alone.

Low road or high road?

The sector and policymakers now face a stark choice regarding the number, size and student profile of universities. In the post-pandemic world, and in the absence of increased direct government funding per student, the sector must choose between the “low road” and the “high road” to survival and sustainability.

The low road would involve pulling back to a largely or even wholly domestic focus. The results would very likely be sector-wide decline, shrinking universities, deteriorating campus facilities, a lowering of horizons and a reversion to a pre-1990s focus on domestic student education.

Read more:

Without international students, Australia's universities will downsize – and some might collapse altogether

Internationalism would give way to isolationism and educational nationalism of Trumpian proportions. This path would consign the sector to a future of parochialism, mediocrity and global irrelevance.

Alternatively, the sector could take the “high road”. This would involve repositioning itself as a high-quality provider of new forms of learning for both international and domestic students.

The sector and government would have to work in partnership to rebuild universities’ global brand and reputation, recover international student numbers and reprofile this student cohort. The latter step would aim both to improve the academic merit of students from China and diversify intakes.

The high road is also the hard road. It requires a pro-active (not defensive) mindset and an all-round shift in perceptions of Australia, Australians and our universities. But it may well set the sector on a bright new path.

The hope that a surge in domestic student demand will save the sector from atrophy is delusional. The government must either greatly increase recurrent funding per student or provide strong tactical support to recover and diversify international student enrolments. The latter approach would enable the sector to continue to cross-subsidise degree studies by domestic students, fund high-quality research, and develop campus and IT infrastructure fit for the fourth industrial revolution.

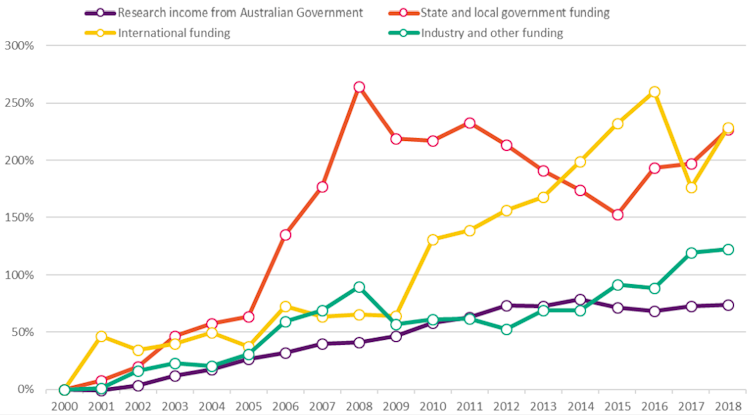

Growth in sources of funding for university research since 2000 (in 2018 dollars)

Universities Australia, CC BY

Read more:

$7.6 billion and 11% of researchers: our estimate of how much Australian university research stands to lose by 2024

The sector can do this without major direct funding increases from a debt-burdened government. But government needs to help the sector help itself.

A 10-point action plan

Universities should act decisively and in concert to:

diversify international students

focus on all-round quality (admission quality, learning quality, graduate outcome quality) of Chinese students

increase strategic partnerships with international institutions as a channel for recruiting high-quality students

leverage international alumni networks more effectively to promote the sector and assist student recruitment and graduate placement

accentuate intensive courses for international students to capitalise on booming demand for life-long learning.

Government could support progress along the high road as follows:

sponsor tripartite trade and education missions to target countries

expand support for intensive study visits

host sector-wide events and promote further learning for international alumni

actively encourage employers to provide in-program placements and onshore post-study work for new international graduates

sponsor initiatives to help graduates secure quality jobs in their home countries.

The sector and government should embrace the high road in partnership. This can only be achieved if we engage in a mature and nuanced discussion about root causes, practical solutions and the sort of university system we really wish to have in this country.

Growth in sources of funding for university research since 2000 (in 2018 dollars)

Universities Australia, CC BY

Read more:

$7.6 billion and 11% of researchers: our estimate of how much Australian university research stands to lose by 2024

The sector can do this without major direct funding increases from a debt-burdened government. But government needs to help the sector help itself.

A 10-point action plan

Universities should act decisively and in concert to:

diversify international students

focus on all-round quality (admission quality, learning quality, graduate outcome quality) of Chinese students

increase strategic partnerships with international institutions as a channel for recruiting high-quality students

leverage international alumni networks more effectively to promote the sector and assist student recruitment and graduate placement

accentuate intensive courses for international students to capitalise on booming demand for life-long learning.

Government could support progress along the high road as follows:

sponsor tripartite trade and education missions to target countries

expand support for intensive study visits

host sector-wide events and promote further learning for international alumni

actively encourage employers to provide in-program placements and onshore post-study work for new international graduates

sponsor initiatives to help graduates secure quality jobs in their home countries.

The sector and government should embrace the high road in partnership. This can only be achieved if we engage in a mature and nuanced discussion about root causes, practical solutions and the sort of university system we really wish to have in this country.

Authors: John Shields, Professor of Human Resource Management and Organisational Studies, University of Sydney