what to do with Roald Dahl's enslaved Oompa-Loompas in modern adaptations?

- Written by Kate Cantrell, Lecturer in Writing, Editing, and Publishing, University of Southern Queensland

The stage adaptation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory has opened in Brisbane. Charlie, like all of Roald Dahl’s novels for children, celebrates courage, resilience and the creative power of childhood.

Charlie Bucket is literally starving to death by the time he arrives at Willy Wonka’s factory. Yet his steely determination to find the last golden ticket, combined with his strong moral compass, sees him emerge as Wonka’s heir, his family’s hero, and the architect of his fate.

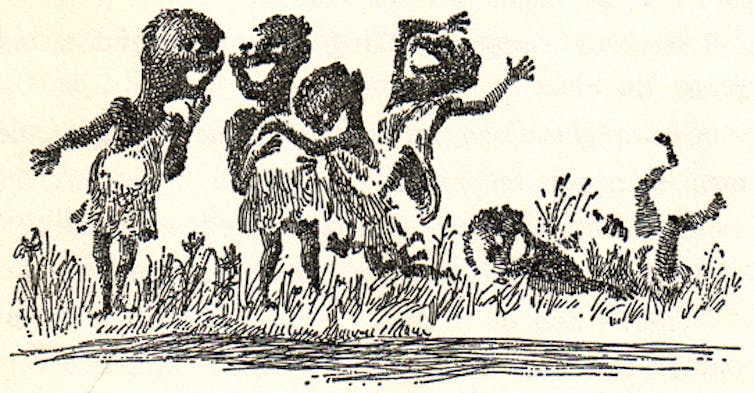

But there is a troubling aspect to this story. In the first edition of Charlie (1964), the Oompa-Loompas are black pygmies who Wonka imports from “the deepest and darkest part of the African jungle” and enslaves in his factory.

In this latest stage production, the Oompa-Loompas are transformed into “humanettes” (living dolls that are part human, part puppet). Their recent manifestation raises a number of questions. What do the Oompa-Loompas represent? And how should they be portrayed in modern-day adaptations?

Read more: Abused, neglected, abandoned — did Roald Dahl hate children as much as the witches did?

Servitude

In the original novel, the Oompa-Loompas work (in lieu of money) in exchange for cocoa beans, the only currency they understand. Wonka explains,

You only had to mention the word ‘cacao’ to an Oompa-Loompa and they would start dribbling at the mouth.

As a messianic figure, Wonka believes he has “rescued” the Oompa-Loompas from certain death. Saving his tiny “helpers” from near starvation, he offers them shelter from their predators, the Snozzwangers and Whangdoodles.

Their servitude, Wonka insists, is a special privilege, a pro-slavery sentiment that echoes the “positive good” defence of the Atlantic Slave Trade.

The Oompa-Loompas as African Pygmies, as depicted by Joseph Schindelman in the original version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964).

AP

The Oompa-Loompas as African Pygmies, as depicted by Joseph Schindelman in the original version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964).

AP

The novel reflects cultural anxieties that emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1960s when the labour market opened to New Commonwealth citizens from India and the Caribbean. Grandpa Joe, a former Wonka employee who is laid off, represents the concerns of white British workers who saw immigrants as rivals for what they believed were rightfully white British jobs.

When Wonka’s factory re-opens with a secret workforce, Charlie says to Grandpa Joe, “But there must be people working there”, and Grandpa Joe responds, “Not people, Charlie. Not ordinary people, anyway”.

Read more: Gobsmacked by Aldi's Revolting Rhymes ban? Try this instead

Whitewashing

In the late 1960s, under mounting pressure to rewrite the Oompa-Loompas, Dahl agreed, in his words, to “de-Negro” his characters.

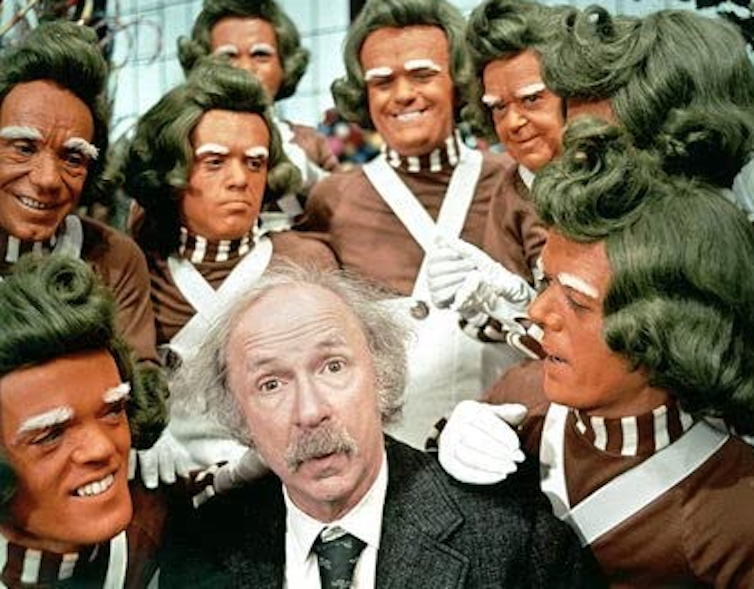

Mel Stuart’s 1971 film adaptation, released in the immediate aftermath of the civil rights movement, recast the Oompa-Loompas as little people with green hair and orange skin. Their homeland is now Loompaland rather than Africa, and they are “transported” to Wonka’s factory rather than “imported”.

The Oompa-Loompas with Grandpa Joe in Mel Stuart’s 1971 film.

Wolper Pictures

The Oompa-Loompas with Grandpa Joe in Mel Stuart’s 1971 film.

Wolper Pictures

This transformation is a textual whitewashing that obscures the power dynamic between Wonka as factory owner and the Oompa-Loompas as his exploited workforce.

Before the film’s release, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the US threatened to boycott cinemas, while the producers worried if they represented black characters in a derogatory way, they would lose revenue.

Dahl eventually buckled to public criticism. In a revised 1973 edition of the book, he reimagined the Oompa-Loompas as “little fantasy creatures”.

In this new edition, the Oompa-Loompas are hippies. Their skin is rosy white; their unkempt hair is golden brown; they frolick in the factory gardens, picking wildflowers, playing hand drums, and chasing butterflies. They symbolise 1970s counterculture and its rejection of materialism, conservative values, and social and political conflict.

Digital clones

In 2005, Tim Burton produced the second cinematic adaptation of Charlie. In Burton’s revision, the Oompa-Loompas are played by a single actor (Gurdeep Roy) who is digitally cloned to create the illusion of a sizeable workforce.

For the first time, the Oompa-Loompas use information technology to communicate wirelessly, enlisting supercomputers to improve their productivity and profits.

In a 2005 interview, Roy recalled Burton’s confirmation that “the Oompas were strictly programmed like robots — all they do is work, work, work.”

“Back off you little freaks!” Mike Teavee derides the Oompa-Loompas as they chastise Augustus Gloop in Tim Burton’s 2005 adaptation.Burton’s adaptation, a commentary on exploited labour in the digital age, shares several thematic concerns with the musical version.

Read more: Cat in a spat: scrapping Dr Seuss books is not cancel culture

Pulling strings

In the Brisbane season, the Oompa-Loompas form a chorus line of hybrid creatures in red curled wigs and identical suits branded with the “W” of Wonka, a stamp marking them as property rather than people.

Each Oompa-Loompa is part human (head and hands) and part puppet (body and legs). The puppeteer manipulates the body and legs to bring the puppet to life.

The result is a bizarre distortion of proportions, in which the Oompa-Loompas burst onto the stage in choreographed song and dance. The theatrical effect is of a stunted character, suspended in space, able to perform gravity-defying dance moves and circus-like tricks.

While the inventive blend of performers and puppets is clever, the puppetry reinstates the power imbalance: Oompa-Loompas are material objects controlled by others.

In attempting to conceal their exploitation, the show’s producers only draw attention to the controversy they are trying to avoid. The fact Wonka’s privilege is never questioned is evidenced by the fact he always remains the same: white, wealthy, and in control.

Using puppets as a way to obfuscate conversation around race has a problematic history in Western theatre. Some theatre-makers insist puppets are essentially “raceless”, but this claim can erase the subject’s potential humanity. An audience isn’t excepted to see puppets as anything other than figures of entertainment.

The fraught history of the Oompa-Loompas captures the irresolvable tension at the heart of children’s literature and theatre: it is impossible to separate children’s stories from the ideological fabric of our world, the power structures that privilege adults, and the particular historical moment in which stories are produced.

Any re-imagining of this classic tale will always be placed in a precarious position.

Authors: Kate Cantrell, Lecturer in Writing, Editing, and Publishing, University of Southern Queensland