Self-employment and casual work aren't increasing but so many jobs are insecure – what's going on?

- Written by David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

That casualisation and self-employment rates are not increasing is often trotted out to dispute perceptions that workplace insecurity is growing.

Read more: Australian jobs aren't becoming less secure

But retorts like this miss a few key points.

First, the real causes of growing insecurity aren’t the type of contracts people are on. While these things matter, the real causes of insecurity are the way organisations are being structured these days. This is designed to minimise costs, transfer risk from corporations to employees, and centralise power away from employees.

Second, aggregate data mask variations between industries.

Third (and least importantly) there are some measurement issues.

Reducing cost and risk

Large corporations want to minimise their costs and risks, avoid accountability when things go wrong and ensure products have the features they want.

This partially explains the dramatic increase in franchised businesses – the franchisee bears responsibility for scandals such as underpaying workers.

Other corporations call in labour hire companies to take on responsibility for their workers. This cuts costs and transfers risk down the chain – which means jobs are more insecure.

Some set up spin-offs or subsidiaries. Some just outsource to contracting firms, like a German outsourcing company.

Most people working for franchises, spin-offs, subsidiaries and labour hire firms are still employees. It’s more efficient for capital to control workers through the employment relationship than to pay them piece rates as contractors. That would run the risk of worker desertion or of shortcuts affecting quality.

Is casualisation the same as insecurity?

Even employees at the bottom of the supply chain might get annual and sick leave. Offering leave helps attract labour and might be cheaper than paying casual loading.

And there’s no need to hire someone on a casual contract if you can make them redundant when the work dries up — if, for example, you lose your contract with the main parent firm. If your firm can go bankrupt, then you often won’t even have to pay redundancy benefits.

There are also the measurement issues. The Australian Bureau of Statistics counts the number of “employees without paid leave entitlements”. People take this to mean “casuals”. On this measure, the share of casuals in the workforce has shifted little in a decade, after growing substantially earlier.

Read more: FactCheck: has the level of casual employment in Australia stayed steady for the past 18 years?

If we take the liberty of labelling people without leave as “casuals”, then the number of “casual” full-timers grew by 38% between 2009 and 2017. Labour hire workers are usually casual full-time workers.

“Permanent” full-timers (those with annual leave) grew by just 10%.

On the other hand, some organisations have found relying on part-time casuals counterproductive, as workers had no commitment and became unreliable. Some large retailers now use “permanent” part-timers rather than casuals.

So-called “casual” part-timers grew by just 13% between 2009 and 2016. “Permanent” part-timers grew by 36%.

A lot of variation between industries and periods is hidden by aggregate figures. Franchising has grown in retailing. Labour hire in mining. Outsourcing in the public sector. Second jobs in manufacturing. Spin-offs in communications. Casualisation in education and training. Global supply chains send jobs overseas to low-paid, often dangerous workplaces in a number of industries.

The ABS doesn’t measure the precarity of work experienced by people who now work in franchises, spin-offs, subsidiaries or contractor firms. But as their continued employment depends on the fortunes of their direct employer, more than the firm at the top of the chain, precarity is real.

Read more: Precarious employment is rising rapidly among men: new research

Underemployment has grown

Many “permanent” part-time jobs may be good jobs. But the continuing growth of part-time employment is linked to another form of insecurity – underemployment.

Between 2010-11 and 2016-17, the number of hours sought, but not worked, by underemployed people grew by 31%. This is five times the total growth in hours worked.

Large firms don’t even need to spin off workers to smaller business units to make use of underemployment.

There are other important sources of worker insecurity. In Australia, for example, firms can seek to have enterprise agreements terminated, or get a handful of workers to sign new agreements, to cut pay and conditions.

Some firms seek to put employees onto contrived arrangements that make them out to be contractors. Often that’s illegal.

The growing insecurity and hence low power of workers – even those with leave entitlements – helps explain why wage growth is stagnating.

Indeed, the successful “war on wages” may be the biggest sign of worker insecurity.

And what about the gig economy?

The gig economy, or more accurately the platform economy, is a big challenge to the employment relationship. This is because virtual platforms provide a new, cheap form of control that may replace the need for the employment relationship.

But there are still limits to the use of cost cutting and of platform control. The gig economy will grow, but it won’t overtake the employment relationship.

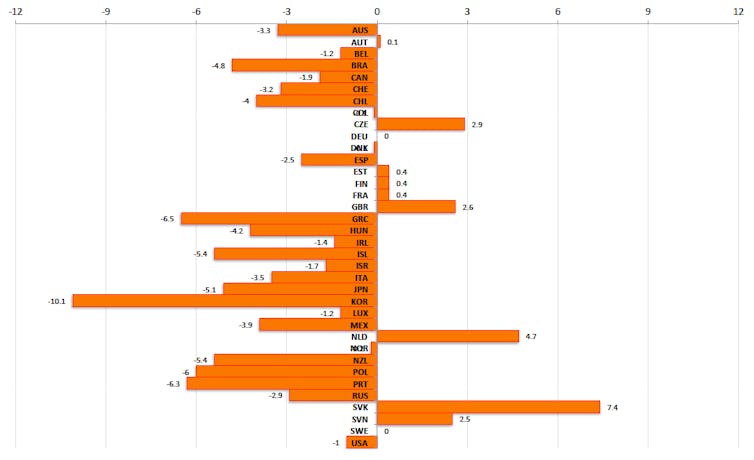

Gig work is one form of self-employment and we should remember that, overall, self-employment is not increasing. Self-employment declined between 2000 and 2014 in 26 countries for which data were available, and increased in only 11 (see chart below).

Changes in self-employment, 2000-2014, various countries. OECD, Author provided

Changes in self-employment, 2000-2014, various countries. OECD, Author provided

What’s more, even the relative importance of large firms in total employment is not decreasing. That’s probably because of another trend — the concentration of markets in the hands of those firms.

In short, large powerful firms are getting more powerful, but their directly employed workforces are not getting larger. The result is a lot of workers with insecure incomes and a lot of insecure small-business owners as well.

This means insecurity gnaws away, even while the employment relationship remains the dominant mode for deploying labour, and employment with leave entitlements remains its main form.

Authors: David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University