At its current rate, Australia is on track for 50% renewable electricity in 2025

- Written by Ken Baldwin, Director, Energy Change Institute, Australian National University

The Australian renewable energy industry will install more than 10 gigawatts of new solar and wind power during 2018 and 2019. If that rate is maintained, Australia would reach 50% renewables in 2025.

The recent demise of the National Energy Guarantee saw the end of the fourth-best option for aligning climate and energy policy, following earlier vetoes by the Coalition party room on carbon pricing, an emissions intensity scheme, and the clean energy target.

Read more: The renewable energy train is unstoppable. The NEG needs to get on board

Yet despite the federal government’s policy paralysis, the renewable energy train just keeps on rolling.

Our analysis, released today by the ANU Energy Change Institute, shows that the Australian energy industry has now demonstrated the capacity to deliver 100% renewable electricity by the early 2030s, if the current rate of installations continues beyond the end of this decade.

Record-breaking pace

Last year was a record year for renewable energy in Australia, with 2,200 megawatts of capacity added. Based on data from the Clean Energy Regulator, during 2018 and 2019 Australia will install about 10,400MW of new renewable energy, comprising 7,200MW of large-scale renewables and 3,200MW of rooftop solar (see charts below). This new capacity is divided roughly equally between large-scale solar photovoltaics (PV), wind farms, and rooftop solar panels. This represents a per-capita rate of 224 watts per person per year, which is among the highest of any nation.

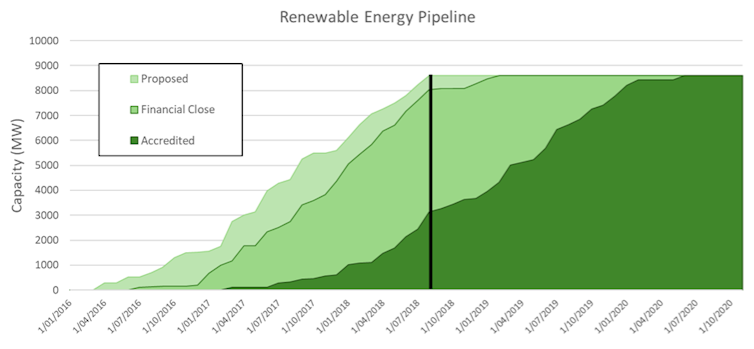

Actual and probable deployment of large-scale (more than 0.1MW) systems in Australia. About 4,000MW per year is currently being installed.

Clean Enegy Regulator/ANU, Author provided

Actual and probable deployment of large-scale (more than 0.1MW) systems in Australia. About 4,000MW per year is currently being installed.

Clean Enegy Regulator/ANU, Author provided

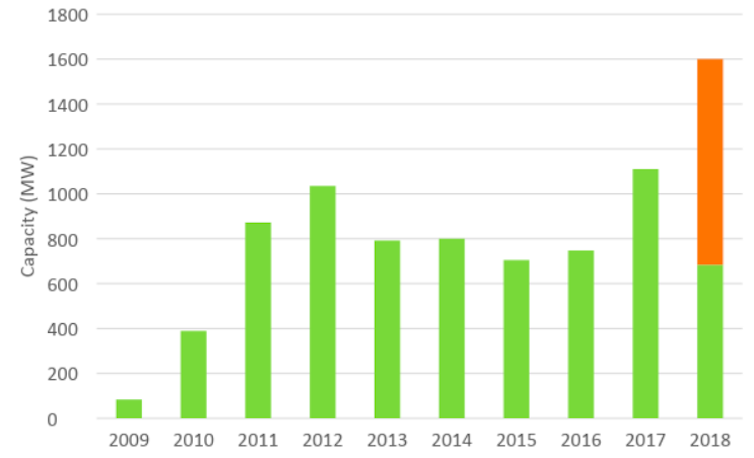

Annual small-scale (less than 0.1MW) rooftop PV capacity additions including an estimate of 1,600MW for the whole of 2018 based on installations for the year to June.

Clean Energy Regulator/ANU, Author provided

Annual small-scale (less than 0.1MW) rooftop PV capacity additions including an estimate of 1,600MW for the whole of 2018 based on installations for the year to June.

Clean Energy Regulator/ANU, Author provided

If the current rate of renewable energy installation continues, Australia will eclipse the large-scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET), reaching 29% renewable electricity in 2020 and 50% in 2025. It may even surpass the original 41 terawatt-hour (TWh) target, which was downgraded by the Abbott government to the current 33 TWh.

Our projections are based on the following assumptions:

demand (including behind-the-meter demand) remains constant. Demand has changed little in the past decade

large- and small-scale solar PV and wind power continue to be deployed at their current rates of 2,000MW, 1,600MW and 2,000MW per year, respectively

large- and small-scale solar PV and wind continue to have capacity factors of 21%, 15% and 40%, respectively

existing hydro and bio generation remains constant at 20 terawatt-hours per year

fossil fuels meet the rapidly declining balance of demand.

No subsidies needed

Renewable energy developers are well aware of these projections, which indicate that they believe that little or no financial support is required for projects to be competitive in 2020 and beyond.

Indeed, the current price of carbon reduction from the government’s existing Emissions Reduction Fund (A$12 per tonne, equivalent to A$11 per MWh for a coal-fired power station (at 0.9 tonnes per MWh), would be sufficient to finance many more renewable energy projects.

The current deployment rate might continue because:

large-scale generation certificates will continue to be issued by the Clean Energy Regulator to accredited new renewables generators right up until 2030

renewable investment opportunities are broadening beyond the wholesale electricity market, as companies value the economic benefits and green profile of renewable energy supply contracts. For example, British steel magnate Sanjeev Gupta has announced plans to install more than 1GW of renewable energy at the Whyalla steelworks, and Sun Metals in Townsville has already installed 125MW of solar capacity

the price of wind and PV will continue to fall rapidly, opening up further market opportunities and putting downward pressure on electricity prices

increased use of electric vehicles and electric heat pumps for water and space heating are expected to increase electricity demand. This increased demand is expected to be met by wind and solar PV, which represent almost all new generation capacity in Australia

retiring existing coal power stations are being replaced by PV and wind.

A renewables-powered grid

As the electricity sector approaches and exceeds 50% renewables, more investment will be required in storage (like batteries and pumped hydro) and in high-voltage interconnections between regions to smooth out the effects of local weather and demand.

We have previously shown the hourly cost of this grid balancing is about A$5 per MWh for a renewable energy fraction of 50%, rising to A$25 per MWh at 100% renewables.

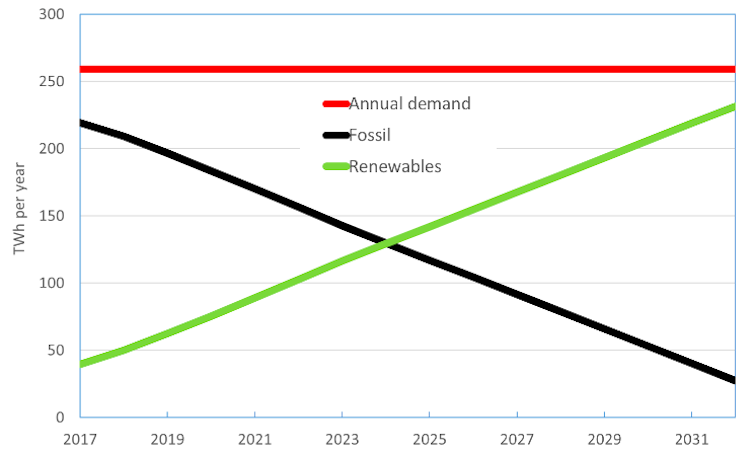

Modelled increase in annual PV and wind generation (TWh) and the consequent reduction in fossil generation based on extrapolation of current industry deployment rates for renewables.

ANU, Author provided

Modelled increase in annual PV and wind generation (TWh) and the consequent reduction in fossil generation based on extrapolation of current industry deployment rates for renewables.

ANU, Author provided

What do our projections mean for Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions? In 2017 these emissions were 534 megatonnes (MT). Under the Paris Agreement, Australia has undertaken to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 26%, from 612MT per year in 2005 to 453MT per year by 2030. This is a reduction of 81MT per year from current emissions.

We assume that all emission reductions are obtained within the electricity system through progressive closure of black coal power stations, which emit an average of 0.9 tonnes of carbon dioxide per MWh of electricity.

On this basis, emissions in the electricity sector will decline by more than 26% in 2020-21, and will meet Australia’s entire Paris target of 26% reduction across all sectors of the economy (not just “electricity’s fair share”) in 2024-25.

Read more: The government is right to fund energy storage: a 100% renewable grid is within reach

Our analysis shows Australia’s renewable energy industry has the capacity to deliver deep and rapid emissions reductions. Direct government support for renewables would help, but it is no longer vital.

Government support for stronger high-voltage interstate interconnectors and large-scale storage projects (like the Snowy 2.0 pumped hydro proposal) will allow 50-100% renewables to be smoothly integrated into the Australian grid. What is crucial is government policy certainty that will enable the renewable industry to realise its potential to deliver deep emissions cuts.

Authors: Ken Baldwin, Director, Energy Change Institute, Australian National University