More students are going to university than before, but those at risk of dropping out need more help

- Written by Andrew Norton, Higher Education Program Director, Grattan Institute

Enrolments to Australian public universities boomed during the last decade. This was due to a government policy known as “demand driven funding”, which between 2012 and 2017 allowed universities to enrol unlimited numbers of domestic bachelor-degree students.

In 2017, 45% more students started a bachelor degree than a decade earlier.

Boosting higher education participation rates, particularly for students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, was one of the policy’s aims. But the Productivity Commission has today given the demand driven system a “mixed report card”.

The report estimates that six in ten school leavers now go to university by age 22, up from a little over half in 2010. But student outcomes deteriorated from their pre-demand driven peaks. Drop-out rates increased while employment rates decreased (although the most recent data suggests positive trends).

Read more: Graduate employment is up, but finding a job can still take a while

It’s important to note, however, that higher education participation rates have been trending up in Australia and around the world for decades, despite significant differences in funding policies. Demand driven funding just led to a particularly quick surge in Australia.

As student enrolments in university are likely to increase, so are the downsides that come with this. The system needs to put in place better measures to help students at risk of dropping out.

The Productivity Commission’s report

Many of the broad conclusions of The demand driven university system: a mixed report card are not new. But the Productivity Commission explored them in depth by tracking young Australians through their final years of school and up to age 25, using the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth (LSAY).

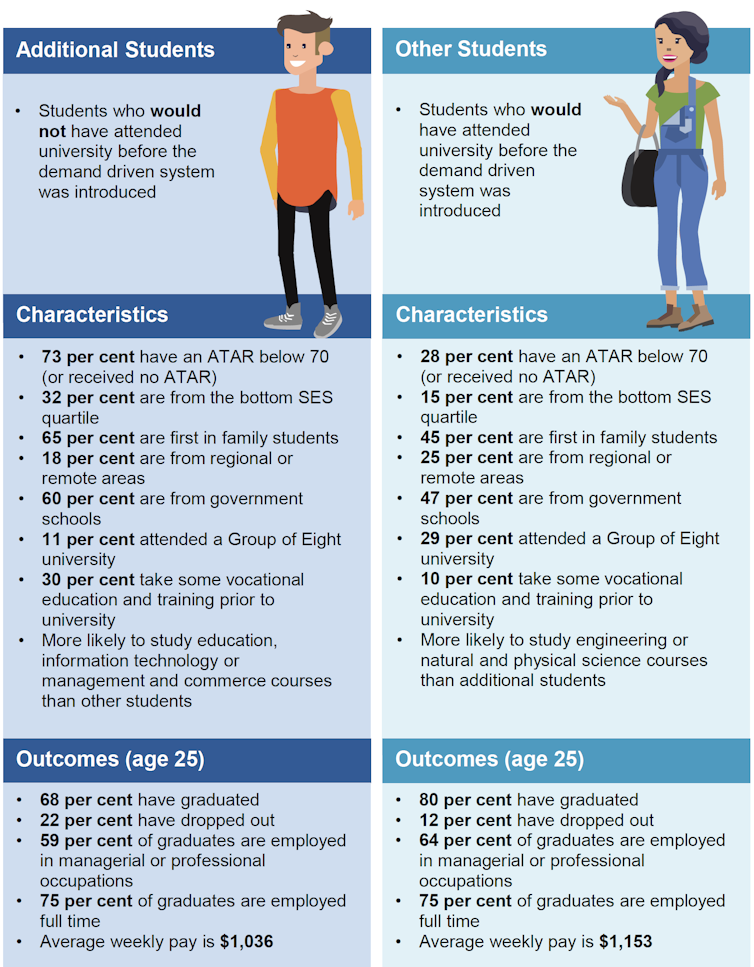

The report used the LSAY data to perform what’s known as a multivariate regression analysis to calculate the “additional students” – which are the students who probably wouldn’t have gone to university without demand driven funding. It compared them to “other students”, who would have enrolled anyway.

Additional student analysis can be useful because, at a system level, good outcomes can hide poor results for more vulnerable groups of students.

The analysis revealed significant differences between the two groups. Nearly three-quarters of additional students had no ATAR or an ATAR below 70, compared to just over one quarter of other students.

Additional students were more likely to come from a low socioeconomic status background (which was one of the aims of demand driven funding), to have attended a government school, and to be the first in their family to attend university.

But additional students were less likely to come from a regional area.

Productivity Commission, The demand driven university system: a mixed report card (screenshot)

Compared to the students who would have gone to university anyway, overall outcomes for additional students were less positive. They were more likely to drop out, and if they did finish their course, were slightly less likely to work in a professional or managerial job than other students.

On average, additional students earned just over A$100 a week less at age 25 than other students. Rates of full-time work were identical for the two groups at 75%.

Because university participation rates are trending upwards anyway, the relevance of additional student analysis goes beyond debates about demand driven funding, which Labor promised to restore if it won office in the May 2019 election. Each wave of expansion brings similar concerns about entry requirements and outcomes, which means we need to think about how to better help at-risk students.

Read more:

Labor wants to restore 'demand driven' funding to universities: what does this mean?

How to help students at risk

On the Productivity Commission’s analysis, a clear majority of additional students did get benefits. Most of them (68%) completed a course, while 59% found the professional or managerial work to which university students typically aspire.

But additional students also faced an elevated risk, compared to other students, of not getting the hoped-for outcomes.

Although that greater risk is not surprising, we should do what we can to reduce it. The Productivity Commission’s report observes improved school achievement would make a difference to poor outcomes, such as university drop out rates.

This is because, on its analysis, weaker academic preparation is the source of much – but not all – of the participation and achievement gap between student groups.

But the Commission also acknowledges improving school achievement is not easy. It has been the generally unsuccessful goal of schools policy for a long time. There are other, easier, ways to manage student risk, which can be done quickly, and would provide immediate benefits.

Read more:

NAPLAN 2017: results have largely flat-lined, and patterns of inequality continue

Diverting students with weaker academic backgrounds to preparatory courses before starting a bachelor degree can help. These courses were omitted from the demand driven system and either had capped student numbers or high fees. They should be made more accessible.

We can also give students better advice on the practicalities of study. Studying part-time creates a high risk of not completing a course. If students were aware how high that risk was – less than 30% of bachelor-degree students who continuously study part-time finish a course – they might find a way to enrol full-time, or decide to do something else.

When study plans aren’t working out, we can do more to protect students from unnecessary costs and debt. The report suggests course counselling so that students “fail fast, fail cheap”. But we can also act before students fail.

Universities could be required to check that students are on track by the census date – the day usually about four weeks into the teaching term when students become liable to pay their student contribution. If students aren’t actively studying, or have no realistic prospect of passing a subject, they should be encouraged to drop it before they incur a debt.

While many students take advantage of the census date, Grattan Institute research found it was not as well understood as it should be. As a result, students end up paying for subjects they don’t want to complete.

A simple name change to highlight the census date’s financial significance, such as “payment date” would help.

Practical measures such as these would preserve the benefits of expanded access to higher education, while reducing its costs and risks. They are worth doing whether we keep current government controls on enrolment expansion or go back to the demand driven system.

Productivity Commission, The demand driven university system: a mixed report card (screenshot)

Compared to the students who would have gone to university anyway, overall outcomes for additional students were less positive. They were more likely to drop out, and if they did finish their course, were slightly less likely to work in a professional or managerial job than other students.

On average, additional students earned just over A$100 a week less at age 25 than other students. Rates of full-time work were identical for the two groups at 75%.

Because university participation rates are trending upwards anyway, the relevance of additional student analysis goes beyond debates about demand driven funding, which Labor promised to restore if it won office in the May 2019 election. Each wave of expansion brings similar concerns about entry requirements and outcomes, which means we need to think about how to better help at-risk students.

Read more:

Labor wants to restore 'demand driven' funding to universities: what does this mean?

How to help students at risk

On the Productivity Commission’s analysis, a clear majority of additional students did get benefits. Most of them (68%) completed a course, while 59% found the professional or managerial work to which university students typically aspire.

But additional students also faced an elevated risk, compared to other students, of not getting the hoped-for outcomes.

Although that greater risk is not surprising, we should do what we can to reduce it. The Productivity Commission’s report observes improved school achievement would make a difference to poor outcomes, such as university drop out rates.

This is because, on its analysis, weaker academic preparation is the source of much – but not all – of the participation and achievement gap between student groups.

But the Commission also acknowledges improving school achievement is not easy. It has been the generally unsuccessful goal of schools policy for a long time. There are other, easier, ways to manage student risk, which can be done quickly, and would provide immediate benefits.

Read more:

NAPLAN 2017: results have largely flat-lined, and patterns of inequality continue

Diverting students with weaker academic backgrounds to preparatory courses before starting a bachelor degree can help. These courses were omitted from the demand driven system and either had capped student numbers or high fees. They should be made more accessible.

We can also give students better advice on the practicalities of study. Studying part-time creates a high risk of not completing a course. If students were aware how high that risk was – less than 30% of bachelor-degree students who continuously study part-time finish a course – they might find a way to enrol full-time, or decide to do something else.

When study plans aren’t working out, we can do more to protect students from unnecessary costs and debt. The report suggests course counselling so that students “fail fast, fail cheap”. But we can also act before students fail.

Universities could be required to check that students are on track by the census date – the day usually about four weeks into the teaching term when students become liable to pay their student contribution. If students aren’t actively studying, or have no realistic prospect of passing a subject, they should be encouraged to drop it before they incur a debt.

While many students take advantage of the census date, Grattan Institute research found it was not as well understood as it should be. As a result, students end up paying for subjects they don’t want to complete.

A simple name change to highlight the census date’s financial significance, such as “payment date” would help.

Practical measures such as these would preserve the benefits of expanded access to higher education, while reducing its costs and risks. They are worth doing whether we keep current government controls on enrolment expansion or go back to the demand driven system.

Authors: Andrew Norton, Higher Education Program Director, Grattan Institute