Food is belonging, otherness and a ‘glorious addiction’ for Melissa Leong and Candice Chung

- Written by Lauren Samuelsson, Associate Lecturer in History, University of Wollongong

Food can bring us together. It carries memories and meaning. And it’s at the centre of new memoirs by food writers Melissa Leong and Candice Chung. They explore the ways food can inspire us to take chances and to heal, and to say the unsayable.

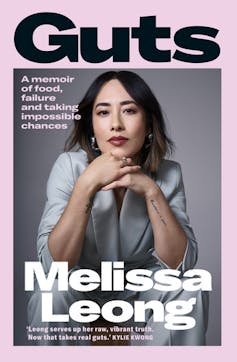

Melissa Leong is perhaps best known for being the first MasterChef Australia judge to be a woman – and a person of colour. In her memoir, Guts, she reflects on her time on MasterChef (among other shows), and her life in the world of food more broadly.

Review: Guts – Melissa Leong (Murdoch Books); Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You – Candice Chung (Allen & Unwin)

Leong started her food writing career during a brief stint in corporate advertising. In 2007, she was encouraged to create something new – a blog! Fooderati was born. From there, she entered freelance food writing, mentored by industry heavyweights Helen Greenwood and John Newton.

Leong claims she “conned” her way into the food world, but reflects, “even before food became a defining part of my career, it was a guiding light in my life”.

A ‘normal family’ at the restaurant

While Leong’s memoir spans her entire career to date, Chung’s is more focused, centring mainly on her experiences over two years, interspersed with stories from the past. In Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You, writer, editor and restaurant reviewer Chung, now based in Glasgow, takes us back to 2019, “the summer of bushfires”, when Sydney was burning.

Since the demise of her 13-year relationship several years prior, Chung had been accompanied on her restaurant review outings by her parents – whom she had been estranged from for a decade. According to Chung, by 2019 they were the perfect team, despite their long estrangement. She writes:

No one ever suspects we are working undercover […] No one ever asks – not even once – why we stopped setting foot in each other’s kitchens for thirteen years. At the restaurant, we are a normal family.

Into this tense equilibrium enters “the geographer”, a Canadian who “messages in full sentences”. On the cusp of the pandemic, she falls in love with him over fried mackerel and green beans, and margarita pizza.

While these books are very different, together they emphasise some key themes about food, belonging, family, mental health and working in the food industry.

Lunch stories and food romance

Leong is the child of Singaporean migrants, who seemingly inexplicably put down roots in Sydney’s Sutherland Shire, “home of The Sharks and the Cronulla riots”. Leong muses they were “committed to the full Aussie experience”. However, being one of very few Chinese children in her primary school was difficult and often hurtful.

The school lunchbox was a symbol of “otherness” for Leong – and many other “ethnic kids” whose daily lunch lacked the ubiquitous, “normal” devon and tomato sauce sandwich.

Lunch is also a key memory for Chung, who migrated to Australia from Hong Kong aged 12. She calls that first year “the year of frozen sandwiches”. Her mother, “inspired by the school canteen’s frozen poppers”, froze ham sandwiches to stop them from spoiling “under the harsh Australian sun”.

Food is the way Chung remembers this period of massive change. It is punctuated with questions of why Australians called dinner “tea”, or recalling the violent disappointment of trying a new Cantonese barbecue place, which served up char siu vastly inferior to that of her “home” in Hong Kong.

For both these women, navigating the way food symbolised their belonging in broader Australian culture was sometimes difficult, but it was also a way they connected (and connect) with their friends, family and culture. It is part of their identities.

As Leong wrote:

No Singaporean I know eats purely for sustenance. It is in our DNA to be obsessed and all-consumed by the romance of food. It is a glorious addiction, the indulgence and the rapture of a really good meal in all its sensorial glory.

Food and family

If food and culture are intertwined in these memoirs, perhaps food and family are even more so. Both authors have complex, complicated relationships with their families, largely stemming from their cultural backgrounds. The difficulty they feel communicating deep feelings with their families is clear. However, there is very little that can’t be said with food.

For Leong’s family, food is “a way of communicating deep love and affection in a culture that often finds it difficult to do so”. She writes that “even if we couldn’t find the words, the simple act of eating together somehow brought life back into perspective, a balm to ease the rifts between generation and culture”.

Chung’s relationship with the “psychic reader”, whom she moved out of home to be with, sneaking away in the middle of the night, led to estrangement from her parents in her early 20s. She and the “psychic reader” would teach each other “how to make the things we remembered eating when we were happy, and when we were heartsick”, she writes. “In the kitchen, we never lost the company of our families.”

Food was her connection to those she loved, while distanced from them.

“Lost in the sauce”

When she reconnects with her parents, Chung finds it difficult to speak to them about her mental health, despite acknowledging her mother also battled depression during “the year of frozen sandwiches”. Of course, in the early 1990s, “no one in our family had heard of depression”, she writes.

These memoirs also convey a sense of the precarity of working in food media. On the eve of Covid lockdowns, Chung faced the probability of the newsroom – and restaurants – being closed down by the virus. Enveloped by the “dread of losing precious work”, she visited the cafes and restaurants she had been eyeing for months, with “the panic of an overzealous tourist”.

MasterChef was an occupational buffer for Leong during Covid. But as an intensely private person working in the public eye, public and journalistic criticism was difficult to take. Facing the end of her tenure as a judge, after the death of co-judge Jock Zonfrillo in 2023, she turned once more to freelancing.

The media couldn’t understand her decision, she writes. But for Leong, this was just another step in her long freelancing career. There is “uncertainty involved in where the work comes from next”, but it is always thrilling.

Fighting for the life you want

Both of these memoirs are captivatingly written – as you might expect from women who have spent years communicating the taste, feel and emotion of food.

Leong’s memoir feels like a punch to the “guts” – short, sharp, sometimes chaotic. Chung’s is poetic and dreamlike, illustrated with verse and vignettes, and a particularly delicious “choose-your-own-adventure” chapter. It’s titled “Self-help meal”: the Cantonese phrase for “buffet”.

Guts is peppered with recipes Leong has developed over many years, which reflect each segment of her story. Just a couple: Pork and prawn wontons with chilli oil and black vinegar, Life’s-too-short-eat-the-cheeseburger-taco.

The trope of “food is love” is perhaps a little overused. But in both these memoirs, you can feel the truth behind it. Leong’s book, she writes, “is ultimately a love story about food, feeling and fighting for the life you really want”.

For both writers, food is love, but it is also more complicated. It is their livelihood, a place of independence, a way of communicating – and their connection to family and culture.

Authors: Lauren Samuelsson, Associate Lecturer in History, University of Wollongong

These memoirs also convey a sense of the precarity of working in food media. On the eve of Covid lockdowns, Chung faced the probability of the newsroom – and restaurants – being closed down by the virus. Enveloped by the “dread of losing precious work”, she visited the cafes and restaurants she had been eyeing for months, with “the panic of an overzealous tourist”.

MasterChef was an occupational buffer for Leong during Covid. But as an intensely private person working in the public eye, public and journalistic criticism was difficult to take. Facing the end of her tenure as a judge, after the death of co-judge Jock Zonfrillo in 2023, she turned once more to freelancing.

The media couldn’t understand her decision, she writes. But for Leong, this was just another step in her long freelancing career. There is “uncertainty involved in where the work comes from next”, but it is always thrilling.

Fighting for the life you want

Both of these memoirs are captivatingly written – as you might expect from women who have spent years communicating the taste, feel and emotion of food.

Leong’s memoir feels like a punch to the “guts” – short, sharp, sometimes chaotic. Chung’s is poetic and dreamlike, illustrated with verse and vignettes, and a particularly delicious “choose-your-own-adventure” chapter. It’s titled “Self-help meal”: the Cantonese phrase for “buffet”.

Guts is peppered with recipes Leong has developed over many years, which reflect each segment of her story. Just a couple: Pork and prawn wontons with chilli oil and black vinegar, Life’s-too-short-eat-the-cheeseburger-taco.

The trope of “food is love” is perhaps a little overused. But in both these memoirs, you can feel the truth behind it. Leong’s book, she writes, “is ultimately a love story about food, feeling and fighting for the life you really want”.

For both writers, food is love, but it is also more complicated. It is their livelihood, a place of independence, a way of communicating – and their connection to family and culture.

Authors: Lauren Samuelsson, Associate Lecturer in History, University of Wollongong