Farewell Ursula Le Guin – the One who walked away from Omelas

- Written by Christopher Benjamin Menadue, PhD Candidate, Literature and Society, James Cook University

Fantasy and science fiction author Ursula Le Guin has died, aged 88. © 2014 Jack Liu

Fantasy and science fiction author Ursula Le Guin has died, aged 88. © 2014 Jack LiuAuthor Ursula Kroeber Le Guin has been the subject of critical debate, analysis and discussion for generations. She died this week at the age of 88.

Le Guin published her first paid work April in Paris in the September 1962 issue of the magazine Fantastic Stories of the Imagination - and I am the proud owner of an original copy. I am a lifelong Le Guin fan, but also an academic exploring how science fiction is a cultural artefact that acts as a lens on changing attitudes and specific issues of its time. For me, Le Guin hit the sweet spots of her time powerfully and frequently.

Le Guin explored what it is to be human, faults and all, and the impact and influence of her work is undeniable in the world of fantasy and science fiction.

Read more: Science fiction helps us deal with science fact: a lesson from Terminator's killer robots

A fantasy writer for all ages

I first encountered Le Guin as a child through the Earthsea Cycle, and it set the bar high for what I considered ever after to be good fantasy literature, leaving me disappointed by many otherwise quite respectable authors.

A Wizard of Earthsea, published in 1968, was the first of three books exploring the life of Ged, a young wizard. Spoiler alert: Ged grows and matures into an adult, starting with his attendance at a secretive wizarding school, where he is scarred on the face by a dark power (which he discovered is inextricably linked to him) and that he later defeats.

Tehanu Frontispiece.Charles Vess 2016

Tehanu Frontispiece.Charles Vess 2016If this sounds familiar, you’re not the first to note it. Regarding the story of Ged in A Wizard of Earthsea, Le Guin didn’t say that J.K. Rowling “ripped me off” in her Harry Potter series, but felt that Rowling should have been “more gracious about her predecessors”.

In the Earthsea series, we are introduced to the complex responsibilities of becoming an adult, and asked to consider the values of life and the nature of death. It’s heavy, but significant and humanly realistic reading for a teenager.

Professionalism and style

Le Guin was fiercely protective and supportive of other authors. In 1973, she made a humorous critique of the problems faced by writers trying to make their worlds fantastical and strange in From Elfland to Poughkeepsie, encouraging and emphasising the importance of appropriate style.

Style is something Le Guin seemed to be able to master effortlessly and consistently. I consider her short story Semley’s Necklace – first published in 1964 and later included in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters – to be the finest of its kind in fantasy writing, its crystalline prose equal to Semley’s tragic fate.

Le Guin maintained an interest in encouraging writers and sharing her art. I have an original and much-thumbed copy of the elegantly titled (and naturally masterfully written) Steering the Craft: a 21st Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story, published in 1998: it didn’t make me a better writer, but it made me respect and appreciate the craft of writing.

David Mitchell, author of Cloud Atlas, waxed lyrical about Earthsea. He was one of a range of famous admirers including Neil Gaiman, Stephen Fry and Billy Bragg who have been tweeting their sorrow.

On human nature, science, ethics and duty

For me, Le Guin has been such a powerful influence in science fiction and fantasy literature that I can’t imagine how it might have developed without her.

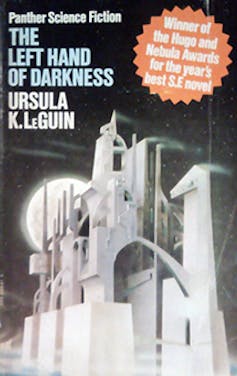

My own much loved, much lent copy of The Left Hand of Darkness (Granada Publishing, 1973).Christopher Benjamin Menadue, Author provided

My own much loved, much lent copy of The Left Hand of Darkness (Granada Publishing, 1973).Christopher Benjamin Menadue, Author providedThe Left Hand of Darkness, published in 1969, inspired and informed a generation of gender writing in fantasy and science fiction. Yet, in her 1976 introduction to this novel, Le Guin maintained that androgyny was not what she considered the theme of the book – it was more to do with essential human feelings about fidelity and betrayal. Her employment of what were to become tropes of science fiction and fantasy was in service of the story, not the other way around, and this was a characteristic of her work.

More than many other author, she employed language, culture and concept in service of writing significant stories about the condition of being human.

Where writer Philip K Dick might be considered the expert of the “what if” scenario in science fiction, for me Le Guin is the expert at “what is?” She asked questions about our nature, aims and desires. She was consistently writing at the coalface of cultural change, or anticipating it.

Read more: Friday essay: science fiction's women problem

Her short story The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas, written in 1973 is a devastating, slow-burn exposition of the implications of taking the utilitarian route in our exploitative relationships with other people.

The power of this writing has only increased with time, as we become more aware of “ethical outsourcing” and labour inequalities. These are portrayed in the film The Last Train Home, where the lives of those in the “developed world” become more comfortable, but at the expense of people we don’t know and can’t see.

The Dispossessed, published in 1974, was my introduction to a reader-friendly explanation of comparative ideologies – I suspect it was the same for many people.

But it was also a story about scientists, and the duty they have to be responsible, ethical and honest. It is another very human story in which Le Guin skillfully portrays the difficulties of presenting complex concepts to an unwelcoming world – something that is still pertinent in an age of climate change denial, anti-vaccination lobbying and fake news.

Le Guin was not a universal fan of scientific progress, but always took a human perspective. She was horrified by the “deal with the devil” of the Google book digitisation project, which although a great technological innovation, she recognised as a potential assault on the rights of authors.

Fantasy and science fiction author Ursula Le Guin.Copyright Marian Wood Kolisch

Fantasy and science fiction author Ursula Le Guin.Copyright Marian Wood KolischLe Guin was a prolific novelist, and I only realise how small a proportion of her work my collection includes when I look look her up on the Internet Science Fiction Database.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, Le Guin consistently wrote thoughtful and artful science fiction and fantasy throughout her life, without becoming fixed in any particular style.

Like Ged in Earthsea, she matured gracefully and elegantly with age, and continued to be powerful force and influence in the world of science fiction and fantasy writing.

The world has lost a great and influential writer and humanist. When I heard the news of her death I was heartbroken.

Christopher Benjamin Menadue does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Authors: Christopher Benjamin Menadue, PhD Candidate, Literature and Society, James Cook University

Read more http://theconversation.com/farewell-ursula-le-guin-the-one-who-walked-away-from-omelas-90632