Lydia Chukovskaya, editor, writer, heroic friend

- Written by Judith Armstrong, Honorary Fellow of the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne

In a new series, we look at under acknowledged women through the ages.

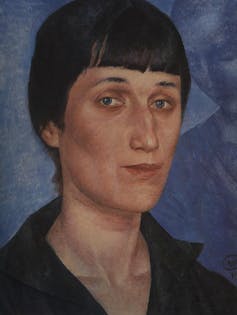

The Russian poet Anna Akhmatova is too tragic and striking a figure ever to be forgotten. A famous portrait depicts her in a midnight blue dress and brilliant yellow shawl beside an objectivist arrangement of lighter blue hydrangeas. Nose aquiline and eyes contemplative under the signature black fringe, she is utterly transfixing. Yet much of our knowledge of Akhmatova is due to the self-effacing journals of a less remembered woman, Lydia Chukovskaya, who brought her friendship, food and unfailing support.

Lydia was a literary editor and a significant poet, novella-writer and memoirist, born in 1907. Her father was Kornei Chukovsky, a prolific and highly regarded writer of much-loved children’s books – a kind of Russian Dr Seuss.

Lydia Chukovskaya.

Wikipedia

Lydia Chukovskaya.

Wikipedia

In cultured St Petersburg, young Lydia developed a passion for literature, but soon after the outbreak of the 1917 Revolution she was briefly exiled to the city of Saratov because one of her friends had used her father’s typewriter to produce an anti-Bolshevik pamphlet.

Permitted to return to newly-named Leningrad, she got a job editing children’s books in the state publishing house, began to write stories, and married a brilliant young physicist, Matvei (Mitya) Bronstein.

Their marriage took place shortly before the outbreak of the Great Terror of 1936-38, one of the most brutal periods in the history of the Soviet Union. Both Mitya Bronstein and Akhmatova’s son Lev were arrested. By the time Chukovskaya was informed that Mitya had been sentenced to ten years in a labour camp, he had in fact been executed. Lev was held in a Leningrad prison for 17 months.

Mitya Bronstein.

Wikimedia Commons

Mitya Bronstein.

Wikimedia Commons

The frantic wife and devastated mother met each other while desperately seeking information about their loved ones. Lydia fled briefly to Kiev, but soon returned to their looted flat in St Petersburg to remake a home with her baby daughter Lyusha. Mitya’s room was occupied by a government surveillant.

Lydia kept a diary, but she now omitted from it everything that was “really important”, including her friendship with Akhmatova, whose intransigence invited arrest at any moment. She knew that to write down their conversations endangered both their lives; yet not to record them, she felt, would be “criminal”. She compromised by waiting until much later to fill in names.

Akhmatova was in the process of writing a long poem, her now-famous Requiem. An extended elegy for all who suffered under the Terror, it was obviously far too dangerous to commit to paper.

When visiting Lydia she would whisper parts of it for Lydia to retain, but in her own bugged apartment she would gesture at the ceiling and say in a loud voice, “Will you have some tea?” while passing over a handwritten page.

Lydia would memorise the poems on it and give it back. “How early autumn has come this year,” Anna would then muse, striking a match and burning the paper over the ashtray.

A 1922 portrait of Anna Akhmatova by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

Wikimedia Commons

A 1922 portrait of Anna Akhmatova by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin.

Wikimedia Commons

‘Hands, match, ashtray’

Lydia wrote of this act of rebellion: “It was a ritual: hands, match, ashtray – a beautiful and mournful ritual”. She would then use her nightly walk home to recall what she had memorised, oblivious to her route. “Poems guided me instead of the moon,” she wrote. “The world was absent”.

Leningrad was yet to experience the extreme shortages of the Siege (1941–1944), but food was far from plentiful. Lydia brought sugar, eggs or rissoles to the impractical Anna, but also lilacs, “so it would seem more like a present”.

During those years she described herself as feeling “less and less alive”, reviving only when she was with Anna,

a certainty amidst all those wavering uncertainties… her words, deeds, head, shoulders and hand-movements possessed of [the] perfection which, in this world, usually belongs only to great works of art.

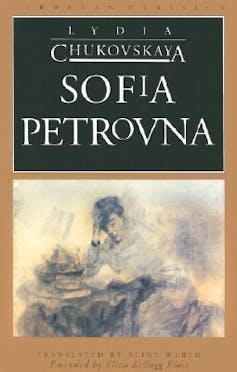

But writing also sustained Lydia’s own spirit. In 1938 she’d been allowed a stint in a writers’ colony where she completed a novella, Sofia Petrovna – naturally unpublishable given that it described the realities of living under the Terror. Sofia is a typist whose son Kolya, a promising engineering student, is arrested.

Sofia embarks on the existence so familiar to Chukovskaya and Akhmatova: frozen hours standing in queues, the lack of news, the attempt to sneak food into the prison. Falling foul of the authorities. When a letter from Kolya finally arrives, Sofia is so terrified of compromising him she forces herself to burn the precious scrap.

After 1956, the year of Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, Sofia Petrovna was circulated in samizdat (manuscript form), and even, during the thaw of the early 60s, came close to publication, but was ultimately rejected for “ideological distortions”. It finally appeared 25 years later, thanks to Gorbachev’s glasnost.

Grit and grief

Chukovskaya’s “acceptable” work included an Introduction to the Ukrainian anthropologist Maclouho-Maclay’s account of life in New Guinea, but her second book, Going Under, published in Paris in 1972, describes how in 1949 Akhmatova and the satirical writer, Mikhail Zoshchenko, were thrown out of the Writers’ Union. She also wrote letters of support regarding Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and the physicist Andrei Sakharov, harassed by the KGB but later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

But writing also sustained Lydia’s own spirit. In 1938 she’d been allowed a stint in a writers’ colony where she completed a novella, Sofia Petrovna – naturally unpublishable given that it described the realities of living under the Terror. Sofia is a typist whose son Kolya, a promising engineering student, is arrested.

Sofia embarks on the existence so familiar to Chukovskaya and Akhmatova: frozen hours standing in queues, the lack of news, the attempt to sneak food into the prison. Falling foul of the authorities. When a letter from Kolya finally arrives, Sofia is so terrified of compromising him she forces herself to burn the precious scrap.

After 1956, the year of Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin, Sofia Petrovna was circulated in samizdat (manuscript form), and even, during the thaw of the early 60s, came close to publication, but was ultimately rejected for “ideological distortions”. It finally appeared 25 years later, thanks to Gorbachev’s glasnost.

Grit and grief

Chukovskaya’s “acceptable” work included an Introduction to the Ukrainian anthropologist Maclouho-Maclay’s account of life in New Guinea, but her second book, Going Under, published in Paris in 1972, describes how in 1949 Akhmatova and the satirical writer, Mikhail Zoshchenko, were thrown out of the Writers’ Union. She also wrote letters of support regarding Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and the physicist Andrei Sakharov, harassed by the KGB but later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

However, her best-known work remains the two volumes recording the almost daily conversations with Akhmatova, an overwhelmingly impressive mix of grit and grief as the two women confronted threats, cold, privation and starvation.

The journals first appeared in Paris in 1976 and 1980, alongside several volumes of autobiographical poetry, On This Side of Death, which express the profound sense of loss that afflicted both her and her country. In 1976 Chukovskaya received the first ever PEN Freedom Prize for the journals, and in 1990, the first Sakharov Prize for her life’s work.

Akhmatova died in 1966; from then on Lydia lived in Moscow, moving between a central flat and her father’s dacha in Peredelkino, the writers’ colony outside the city. She died in 1996, not altogether forgotten, but her memory outdazzled, as she would have deemed appropriate, by that of her more splendid friend.

Quotations from Lydia Chukovskaya, The Akhmatova Journals, Vol. 1, 1938-41, Harvill 1994, tr. Milena Michalski and Sylva Rubashova.

However, her best-known work remains the two volumes recording the almost daily conversations with Akhmatova, an overwhelmingly impressive mix of grit and grief as the two women confronted threats, cold, privation and starvation.

The journals first appeared in Paris in 1976 and 1980, alongside several volumes of autobiographical poetry, On This Side of Death, which express the profound sense of loss that afflicted both her and her country. In 1976 Chukovskaya received the first ever PEN Freedom Prize for the journals, and in 1990, the first Sakharov Prize for her life’s work.

Akhmatova died in 1966; from then on Lydia lived in Moscow, moving between a central flat and her father’s dacha in Peredelkino, the writers’ colony outside the city. She died in 1996, not altogether forgotten, but her memory outdazzled, as she would have deemed appropriate, by that of her more splendid friend.

Quotations from Lydia Chukovskaya, The Akhmatova Journals, Vol. 1, 1938-41, Harvill 1994, tr. Milena Michalski and Sylva Rubashova.

Authors: Judith Armstrong, Honorary Fellow of the School of Languages and Linguistics, University of Melbourne