From 'arse-ropes' to 'flying venom', a history of how we have come to talk about viruses and medicine

- Written by Kate Burridge, Professor of Linguistics, Monash University

Symptom, virus, epidemic, quarantine.

We’ve become used to these terms in 2020. But the “COVID-19 vocabulary” might have been very different had it not been for a few twists and turns in English history.

If history had gone differently, for instance, we might visit the leech about flying venom or gound. But instead we now see the “doctor” about “viruses”.

English has long had a love affair with what linguists rather curiously describe as “borrowing” from other languages (as if we’re giving these words back!). In medical parlance, rare are those Old English survivors like midwife (historically, “with woman”).

To better understand this process, let’s journey to a time in English history when the metaphorical invasion of French words began with a literal invasion of the English homeland. Then, hold onto your arse-ropes (“intestines”) as we imagine an alternative universe in which that invasion never happened — and where we’d be speaking about health and illness in very different, Old English ways!

Read more: Barracking, sheilas and shouts: how the Irish influenced Australian English

Linguistic ‘poverty’ and the French invasion

Many a writer has claimed that English wasn’t up to the task of describing new concepts and feelings, including those linked to health and illness. Francis Bacon described English as a language that “would play the bankrupt with books”. Virginia Woolf believed medicine’s “empathy problem” could be linked to its “poverty of the language”.

For some time now we’ve been looking to other languages to fill this gap — the classical languages of course, but in particular French. After William the Conqueror took the throne following the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the English language was never the same again. The Normans controlled the state, the military, cultural and intellectual interests, and around 10,000 French words flooded into these areas.

After the Norman triumph in 1066, the English language was never the same again.

english-heritage.org.uk

After the Norman triumph in 1066, the English language was never the same again.

english-heritage.org.uk

Among the sciences, medical vocabulary incorporated the largest number of these, and most are still part of modern medical English: surgery, doctor, physician, surgeon, patient, malady, pain, disease, infection, plague, pestilence, pus, pustule, remedy, ointment, medicine and hospital are just a few. Even many of the Latin and Greek medical terms that came into English did so via Anglo Norman.

However, we must be careful not to exaggerate the impoverished state of English vocabulary before the arrival of the French. Many medical expressions would have been redundant borrowings, probably even more than we’re aware of, since our knowledge of Old English is quite limited.

So, what might our COVID-19 vocabulary look like now, if Harold had won the Battle of Hastings and English hadn’t become the linguistic “bitser” it is today?

Exit the French “doctor”, and enter the Old English “leech”

The Old English verb lacnian, meaning “to heal”, inspired more than a few medical terms, including the all-important læce “leech” or “medical practitioner” — a leech of the greatest skill was the heah læce (“high leech”) and one not so skilful the unlæce (“unleech”). Leechcraft was what these leeches practised, leechdoms were their remedies — and leech houses were where they later worked.

And while leech lives on as the “blood-sucking aquatic worm”, most of the Old English terms simply disappeared (læcegetawu “medical instruments”; læcecist “medical chest”; læceseax “lancet”). Of the numerous words for “disease” (adl, untrumness, suht, unhælth), only seocnes (“sickness”) survives. The adligende (“patient”) might be described as unstrang (“unstrong”), unmeaht (“weak”), lef (“injured”), untrymig (“ill”), unhæle (“sick”) or besmitten (“infected”) — of these, just (be)smitten remains, but only as “love-struck”.

“Night walkers” and “flying venoms”: The infectious hellscape of Old English

Not surprisingly, Old English had many terms for infectious disease. Leechbooks flourished with descriptions of assaults by supernatural beings and with constant reminders of the threat from invisible fiends like the niht gengan (“night walkers”) and onflyge (“on-flying things”). Particularly striking were the remedies for fleogendum attre (“flying venoms”). These illnesses were nasty — they arrived out of the blue, and they spread quickly through Anglo-Saxon communities. Undoubtedly among these various on-flying things were airborne viruses or infections.

But fear not, your local, bulk-billing leech might serve up a good treatment from 9th-century Google, Bald’s trusty leechbook:

Wið fleogendan attre asleah IIII scearpan on feower healfa mid æcenan brande geblodga ðone brand weorp on weg sing ðis on III […]

For flying venom, make four incisions in four parts of the body with an oak stick; make the stick bloody; throw it away; sing this three times […]

Certainly, Old English had no shortage of terms for pestilence in its wordhord, among them oncome (“on-come”), cwyld (from cwellan “to kill”), cothe (now a cattle disease) and also uncothe, a particularly malicious version (prefixes such as un- and dis- often intensified a pejorative sense). A strange-looking one was wolness (nothing to do with wellness!).

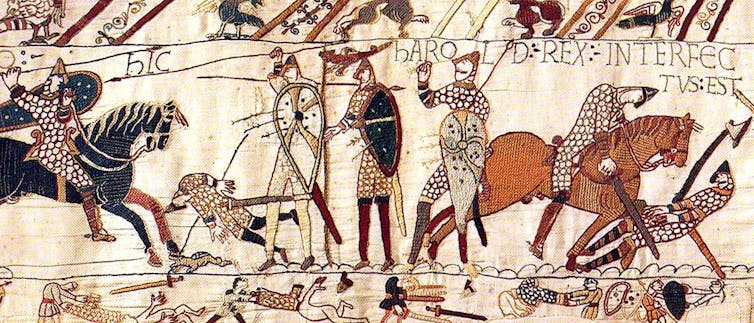

Some medieval medical treatments seemed less than relaxing.

British Library

Some medieval medical treatments seemed less than relaxing.

British Library

Unprecedented ‘viruses’, and noxious ‘sleepy dust’

The influx of French words created the system of levels that characterizes English vocabulary today (and consequently the way we talk about COVID-19). The native English words are typically shorter, more concrete and stylistically more neutral (they include grammatical words like a and the, and of course the obscene ones too). This basic vocabulary supports the lexical superstructure of French and classical words that are more formal, even high-falutin’.

The lofty French/Latin hybrid unprecedented has been shot into linguistic stardom by the current pandemic. It’s hard to imagine any of the native English equivalents (alone, unmatched, makeless, mateless and nonesuch) achieving this level of success.

Lockdown might be pure English, but social and physical distance and even that curve we’ve been hell-bent on flattening are pure French (flatten, though, we owe to the Vikings).

And, of course, there’s “virus” itself. Latin virus appeared in the leechbooks but referred to noxious secretions generally, before it shifted to the actual agent that causes an infectious disease. (As a curious aside, we note that 18th-century viricide was awkwardly ambiguous between the killing of viruses and the killing of husbands). There were plenty of Old English equivalents to virus, but gund stands out. It survived as gound into the 17th century, although it had narrowed in meaning to the gunge that collects in the corners of our eyes.

French and Latin borrowings are here to stay, and while we’ll miss the arse-ropes and wonder why gound ended up just in our eyes, we won’t miss those night walkers.

Read more: Oi! We're not lazy yarners, so let’s kill the cringe and love our Aussie accent(s)

Authors: Kate Burridge, Professor of Linguistics, Monash University