Half a century ago, the Great Barrier Reef was to be drilled for oil. It was saved – for a time

- Written by Rohan Lloyd, Lecturer in Science and Society, James Cook University

At the end of the 1960s, there was every expectation the Great Barrier Reef would be drilled for oil.

The first gas well had been drilled in Victoria’s Bass Strait in 1965 and oil was discovered soon afterwards. Queensland wanted to follow suit. In 1967, the state’s entire coastline was opened to oil exploration.

In August that year, conservationists began fighting to save the reef. Public opinion strongly backed their campaign. Even so, victory was by no means certain.

But in 1975, a national marine park was declared over the Great Barrier Reef, banning oil, gas and mining.

The reef had been saved – for a time. Fifty years later, the Barrier Reef, like coral reefs across the globe, faces the far larger threat of climate change.

It can be easy to look back at history and think what happened was inevitable. But events could very easily have gone down a different path.

How could an immense reef system be vulnerable?

In 1908, the author Edmund Banfield imagined a future where his tropical home, Dunk Island, and neighbouring islands would form part of a “great insular national park”. Ornithologists and nature writers such as Banfield successfully lobbied to protect many of the reef’s islands to save birds from hunters.

Early in the 20th century, turtles were routinely butchered and their meat canned and sent abroad. By the 1950s, public outcry over their treatment and falling numbers prompted governments to severely limit their exploitation.

In 1956, park rangers proposed a national park across the Whitsunday Islands or an even larger area to protect reefs from tourists. Reef-walking and coral-collecting were popular, but rangers and conservationists feared the reef might be loved to death. Authorities restricted shell and coral collecting, but the national park idea went nowhere.

Naturalists and scientists had long known the Great Barrier Reef faced natural threats. In 1925, the naturalist E. H. Rainford observed a “scene of the utmost desolation” after floodwaters covered Whitsunday reefs with silt:

the corals dead, broken to pieces and blackened by decay; the clam shells gaping wide and empty […] a scene with hardly any life in it.

For many, a corals capacity to survive in such conditions was part of their beauty. But in 1960, a new threat emerged – the first recorded crown-of-thorns outbreak. These large coral-eating starfish devastated popular tourist reefs near Cairns.

It shocked people into seeing the entire reef as vulnerable. The future director of the National Museum of Australia, Don McMichael, called for “serious thinking” about the reef’s future.

A reef in need of saving

In 1967, cane growers in Cairns applied to mine lime from Ellison Reef off Mission Beach.

Outraged, the local artist John Busst began organising to stop it. His determination would earn him the sobriquet of the “Bingil Bay Bastard”. Poet-turned-environmentalist Judith Wright, forester Len Webb, and the Queensland Littoral Society soon joined.

Their Save the Reef campaign succeeded in stopping the lime mining – only to find oil and gas drilling posed a new threat.

Their expanded campaign caught the Queensland government flat-footed.

A 1968 cabinet report noted the government was “not well informed” over how much damage the reef could tolerate and had failed to “silence or satisfy the vociferous objections of absolute conservationists”.

Later in 1968, Joh Bjelke-Petersen became the new Queensland premier – a title he would hold for nearly 20 years. Neither he or his deputy, mining minister Ron Camm, had any sympathy for those campaigning to Save the Reef. In fact, Bjelke-Petersen had shares in mining companies with leases over the reef.

What’s more, some reef scientists from the Great Barrier Reef Committee, an influential research group, endorsed the idea of “controlled exploitation” of the reef – including mineral and petroleum resources. This position ruptured relationships between conservationists and scientists.

Meanwhile, the federal government was under increasing pressure from conservationists and the public to stop oil and gas drilling.

It wasn’t clear, though, which tier of government had sovereignty over the reef and its resources. Conservationists believed the federal government had exclusive rights under a United Nations convention on territorial waters. But the Liberal Prime Minister, John Gorton, was unwilling to test the notion.

As the first major reef drilling operations loomed in January 1970, Queensland’s trade union council announced a “black ban” on any ships or rigs used for reef oil exploration. The two companies affected, Ampol and Japex, stopped preparations and called for an inquiry.

Buoyed by public support and positive media coverage, the Gorton government persuaded Queensland to stop all reef drilling pending a joint royal commission.

A state park – or national?

In May 1970, the royal commission began its marathon hearings into petroleum drilling on the reef. Prominent figures such as the first Reserve Bank governor H. C. “Nugget” Coombs gave statements, alongside scientists, mining experts and conservationists.

Coombs told commission members they were “making a judgement […] on behalf of the community as a whole”, while marine biologist Patricia Mather, the secretary of the Great Barrier Reef Committee (now the Australian Coral Reef Society), drafted and tabled legislation for a possible Barrier Reef Act.

It would take four years for the Royal Commission to deliver its report.

During this time, Australia elected its first Labor government in 23 years. The new Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, had big changes planned.

In 1973, the Whitlam government introduced laws asserting Commonwealth control over Australia’s “submerged lands”. It would mean Canberra controlled the Great Barrier Reef’s oil reserves. Queensland and the other five state governments promptly took the matter to the High Court.

In the meantime, the federal government began drafting reef protection laws – based on the submission by marine biologist Patricia Mather.

The Royal Commission handed down its report on oil drilling on 1 November 1974. Of the three members, two accepted some drilling could occur. But the chair, Gordon Wallace, recommended against any oil drilling at all.

Armed with the chair’s recommendation, Whitlam reached out to Bjelke-Petersen to seek Queensland’s cooperation to protect the reef. But the premier was focused on creating a series of state marine parks which would couple oil, gas and mineral mining with stronger protections.

In a letter to Whitlam, Bjelke-Petersen described the prime minister’s actions as “impulsive” and asked him to wait for the High Court decision. He stated his government did not wish to be associated with unconstitutional matters and expected Whitlam would “take a similar responsible attitude”.

Whitlam pressed on. In November 1974, he told The Australian Queensland was being run by “environmental vandals”. The laws were to:

protect an irreplaceable part of Australia’s natural heritage.

In May 1975, the Whitlam government introduced the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Bill to parliament, where it became law. No mining or oil and gas drilling would be permitted.

On November 11, 1975, the Whitlam government was dismissed. The next month, Malcolm Fraser’s Liberal Party was elected. Not long after that, the High Court ruled in favour of federal control of submerged lands.

In the “spirit of cooperation”, Bjelke-Petersen reached out to the new prime minister to gauge his thinking on the reef.

Fraser told him the federal government would push on with its marine park laws – and that there would be no oil and gas extraction or mining in the marine park.

Hard-won protection – for a time

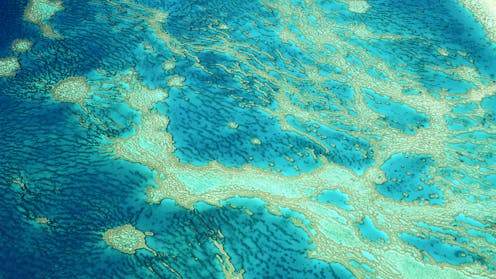

It’s hard not to be impressed by the scale of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park: 344,000 square kilometres – larger than Victoria – 3,000 coral reefs and more than 1,000 islands. But it is the scale of life which enraptures. Above and below the churning ocean and in the blistering sun, it hums with absolute splendour and wonder.

Unfortunately, “saving” the reef doesn’t just have to be done once. All coral reefs face human threats: fishing, coastal development and declining water quality. But these pale compared to the big one – climate change. As intense marine heatwaves multiply, coral bleaches over large areas and can die.

In the 1960s, conservationists fought hard to stop oil and gas on the reef. Their campaign eventually succeeded. But the reef couldn’t escape the damage done by the oil and gas extracted and burned everywhere else. Saving the reef is going to be even harder this time round.

This account draws on the author’s book, Saving the Reef – The human story behind one of Australia’s greatest environmental treasures.

Authors: Rohan Lloyd, Lecturer in Science and Society, James Cook University