how leadership instability and revenge became woven into our political fabric

- Written by Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

Back in 2012, a major study on the selection and removal of party leaders in Anglo parliamentary democracies was published. The book contained a section with the inviting title of “Machiavellian tactics”. Most of the authors’ examples came from Australia.

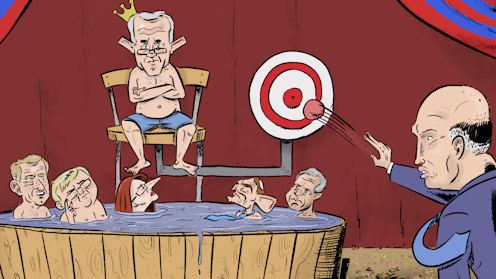

That was then. Since the appearance of that book, Kevin Rudd has tipped out Julia Gillard, and Malcolm Turnbull dispensed with Tony Abbott. Now, Turnbull himself seems in difficulty, as rumours abound of a possible challenge from Peter Dutton.

If Politics at the Centre: The Selection and Removal of Party Leaders in the Anglo Parliamentary Democracies ever appears in a revised edition, William P. Cross and André Blais should thank their lucky stars for Australian democracy. Henry Lawson’s description of the Australian bush springs to mind – “the nurse and tutor of eccentric minds, the home of the weird, and much that is different from things in other lands”.

Read more: View from The Hill – It's time for Turnbull to put his authority on the line

The intensification of leadership churn in recent decades, and especially since 2001, is well documented. After the defeat of Malcolm Fraser at the 1983 federal election, the Liberal Party changed leaders six times, eventually settling on John Howard in 1995. He then led the party for almost 13 years.

Since Brendan Nelson succeeded Howard after the 2007 election, the Coalition has changed leaders three times, including twice between the 2007 and 2010 elections. Following the defeat of Paul Keating’s Labor government at the 1996 election, Labor has had eight leadership changes, a remarkable feat considering that two of those leaders – Kim Beazley and Bill Shorten – have between them tallied up almost 13 years. The rest – Simon Crean, Mark Latham, Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard – do not account for even a full decade between them.

Australia did not begin discarding party leaders and even prime ministers yesterday. Psephologist Malcolm Mackerras suggested during the peak Rudd-Gillard unpleasantness of 2012 that the phenomenon began with the rivalry between John Gorton and Billy McMahon in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

This contest – and the instability to which it contributed – stood in stark contrast to the somnolence of the post-war years, which included the lengthy terms of leadership served by H.V. Evatt (1951-60) and Arthur Calwell (1960-67) during the long Menzies ascendancy (1949-66). The turbulence of the Whitlam leadership was in tune with the post-Menzies times: the Labor leader only narrowly survived a leadership contest with the Left’s candidate, Jim Cairns, in 1968.

But even Gorton was not the first prime minister to win an election only to be discarded by his party. In Australian politics, that honour belongs to Billy Hughes. Forced to resign the prime ministership in 1923 at the instigation of Earle Page, leader of the Country Party, Hughes’s replacement was the wealthy patrician figure of Stanley Melbourne Bruce. Hughes spent the rest of the decade on the backbench, waiting for his revenge. That opportunity eventually came when Bruce tried to transfer most industrial powers to the states. Hughes and a group of dissidents crossed the floor and brought down the government. It’s hard to overlook one or two parallels in this scenario with the current state of play in Australian politics.

Hughes lost his job in large part because of a political realignment that had, in the first instance, placed the former Labor leader at the head of a non-Labor party and in the second instance, because a new force arrived on the scene in the form of the Country Party that was opposed to many of his policies. He might have been the classic “rat”, but even once he switched sides he remained true to many of the policies long favoured by his former party.

Again, it is hard to miss the present-day resonance. Turnbull leads a party with many members – both in parliament and beyond it – who do not see him as one of them. Some see him as Labor in Liberal drag. He has policy preferences that, at least for the right of his party, are as offensive as much that they find in Labor and the Greens.

There is also the cultural issue. Hughes still looked and sounded to many conservatives like the socialist demagogue he once was. Turnbull appears to his internal opponents as a progressive who should have joined the Labor Party, and might as well don his old leather jacket and go back to his friends at Q&A.

Read more: From 'Toby Tosspot' to 'Mr Harbourside Mansion', personal insults are an Australian tradition

But leadership instability isn’t just about leadership. It is about how we do politics. Churn is the result of the potent combination of rolling opinion polls and, in the case of the federal Liberal Party, the sovereignty of the parliamentary party in leadership matters. One of Rudd’s parting gifts to the Labor Party was a change of rules that has greatly increased the transactional costs of leadership changes between elections. Shorten has been the beneficiary. But the Liberals have not travelled down this path, and the destabilisation of Turnbull is one of the results.

This also speaks to a wider crisis in conservative politics. The global populist revolt epitomised in the Anglo democracies by Brexit and Trump is having its effects here. It is doing enormous damage to the cohesion of the Coalition parties, but especially the still fairly broad church of the Liberal Party. News Corp papers are a major player in its internal factional manoeuvring and leadership destabilisation, and there is beyond the parliament a network of radio shock jocks, op-ed columnists, Sky News personalities and think tank “researchers” who have dealt themselves into the Liberal Party’s internal politics.

Ironically, it is starting to look a bit like the Labor Party of the 1960s, an outfit that allowed too many meddlers too great a say in its affairs, until Whitlam and his allies said enough was enough.

For Turnbull, it is starting to look like it might be too late.

Authors: Frank Bongiorno, Professor of History, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University