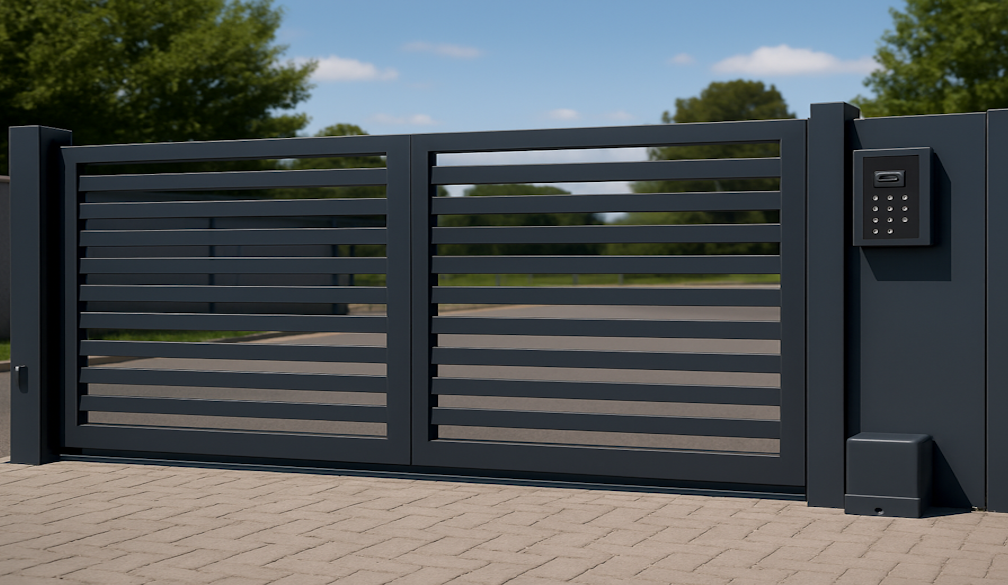

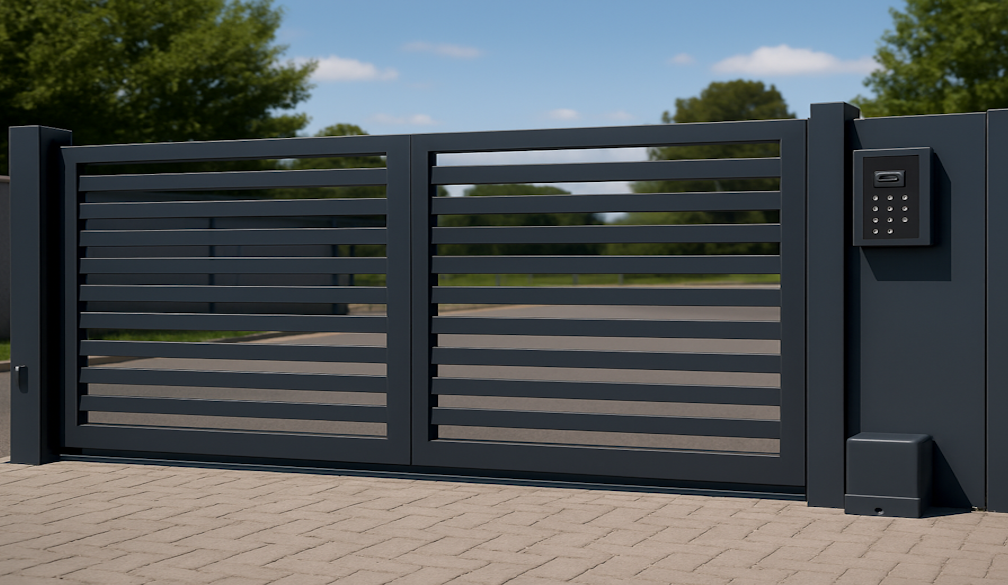

Security and convenience have become defining features of modern properties, and automatic gates Melbourne are increasingly seen as a practical sol...

Office spaces are dynamic environments where people collaborate, meet clients, and spend a significant portion of their day. Maintaining cleanliness...

Losing a single tooth can have a noticeable impact on comfort, appearance, and confidence, which is why a Single Tooth Dental Implant is considered...

Grief rarely moves in a straight line. It doesn’t follow stages neatly, and it doesn’t respond well to pressure — especially the quiet pressure ...

A steel plate is one of those materials that quietly holds the modern world together. It does not demand attention, yet it supports bridges, buildin...

Surgical options for breast enhancement have evolved over time, offering different approaches depending on a person’s goals and body type. One opt...

A shattered side window is more than an inconvenience. Whether caused by a break-in, road debris, or accidental impact, it leaves your vehicle exposed...

Choosing the right platform is a crucial decision for any online business, and Shopify web development has become a popular choice for brands that ...

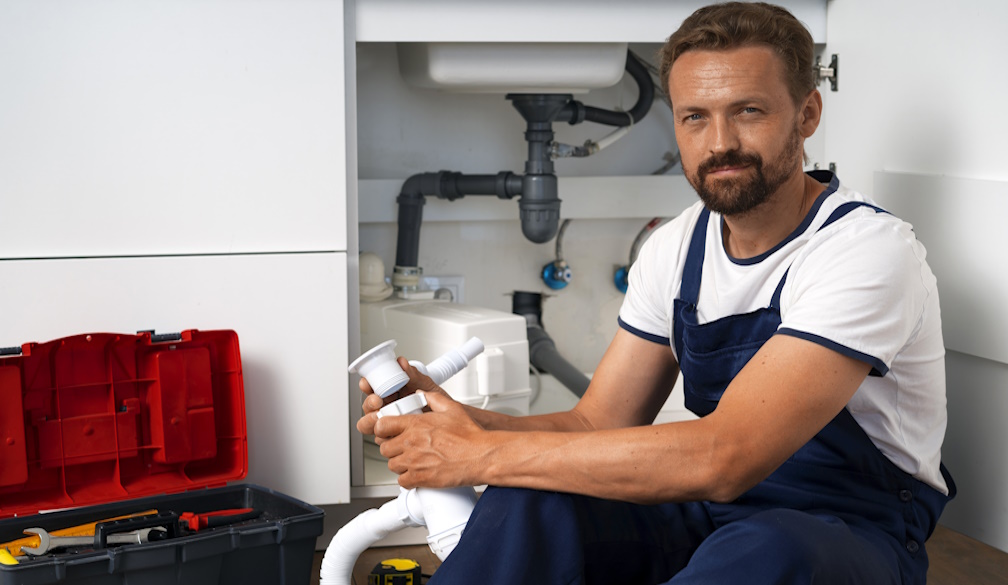

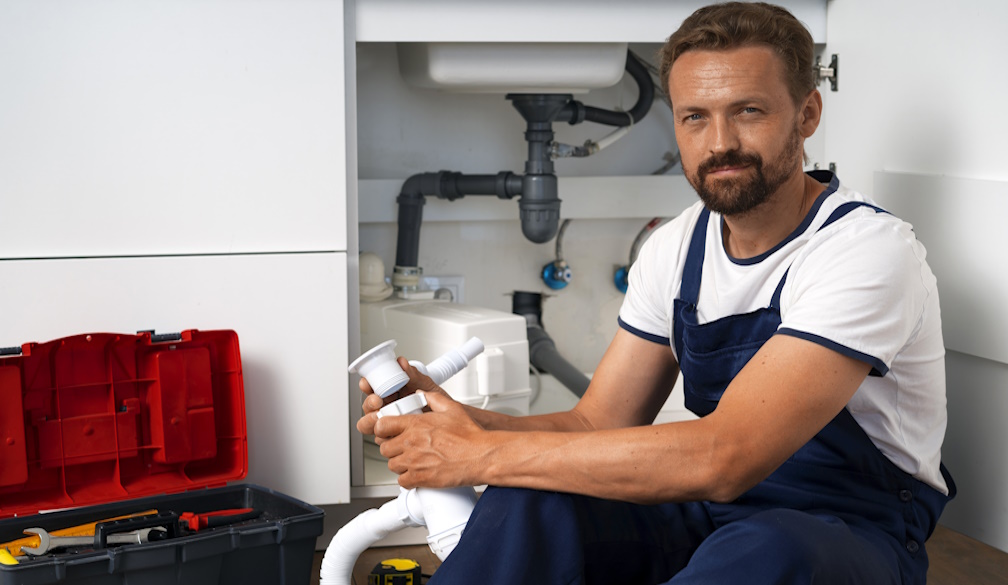

Pipe leaks can be deceptively difficult to spot. Some announce themselves with a steady drip under the sink, but many develop quietly behind walls, ...

If you run a Melbourne business with roughly 7–100 staff, you have probably noticed something over the last couple of years. The IT problems got m...

Indoor air quality (IAQ) plays a crucial role in our health, comfort, and overall wellbeing. Australians spend nearly 90% of their time indoors-at hom...

As energy prices continue to rise and sustainability becomes a priority for Australian homeowners, more families are investing in Solar and Solar Ba...

A sudden plumbing issue can quickly turn into a major disaster if not handled promptly. From burst pipes and overflowing toilets to leaking gas line...

Older homes make up a large part of Melbourne’s housing stock. Victorian terraces, Edwardian houses, Californian bungalows, and post-war brick hom...

Moving to a new home or office can be exciting, but it also comes with stress, planning, and plenty of decisions. One of the most important choices yo...

Choosing the right real estate agent can make a major difference to your final sale price, days on market, and overall experience. The Central Coast...

Imagine a home or commercial space that not only stands the test of time but also tells a story through its very facade. In the world of architectur...

Australia’s vast and varied landscapes invite travellers to explore far beyond sealed roads and crowded parks. Offroad caravans are purpose-built ...

Pietro da Cortona's fresco The Triumph of Divine Providence (1633-1639)Wikiart

Pietro da Cortona's fresco The Triumph of Divine Providence (1633-1639)Wikiart